At 10.30 pm on the night of 21st November 1830, several men met together at a public house called ‘The Powell Arms’, in Birchington, Thanet.

They were all local men aged between seventeen and thirty three: Thomas Hepburn, William Reed, Thomas Overy, Richard Oliphant, Stephen and James Bushell, William Hughes, William Brown, Thomas Golder and William Lilley.

Thomas Hepburn was thirty, a ploughman and wheelwright. His companions included threshers, waggoners, a shoemaker, brick maker and a butcher.

Did Thomas set out to meet those men on that Saturday night or was it a chance encounter? Later, it was claimed that the men had been drinking elsewhere before going on to the Powell Arms; that they were the worse for the drink and had been talking loudly about the injustices in their working life.

Had Thomas been planning deeds born out of desperation when he left home or was he caught up in the wild talk which such heavy drinking groups can generate?

Did he think of the consequences to his family if he were to be caught or was he beyond such sensible thinking?

What drove a man with a young family to take such desperate action that he risked execution, transportation to a penal colony on the other side of the world or, at the very least, jail if he were caught?

Thomas was a married man with two young children. He had married Elizabeth, the daughter of John Emptage and his wife Sarah Impett, in 1825. They were living in Acol. What was going to happen to them?

The Life of the Agricultural Worker

Until 1770 there were many smallholders known as cottagers. Whilst working for a local farmer, they also had their own strips of land on which they could grow crops. They could keep a cow and graze it on common land and thus be able to have milk and make butter and cheese. They kept a pig for meat and chickens for eggs. They could forage for food and could gather wood for fuel. They were self sufficient in food and what they earned from the farmer paid for clothes and furniture.

But, between 1770 and 1830, parliament issued a series of Enclosure Acts whereby the rights of local people to use the open fields and common lands were removed. Some 6 million acres of land were enclosed and divided up amongst the larger local land owners. Thus, many previously self sufficient smallholders had lost their land and were now dependent on those landowners or the tenant farmers.

But whereas farmers had previously provided a full time job with a ’tied’ cottage, they were cutting back on their costs and employing casual workers by the job or the season. Farm workers now found themselves in the position of casual labourers, moving from farm to farm as required instead of having the regular jobs which they had enjoyed before.

By 1830, there had been years of war and high taxes, three years of poor harvests (which meant less income) and their living conditions were poor (very often little more than hovels).

And now the agricultural labourers faced a winter of very little income due to the introduction of mechanisation and even more hardship.

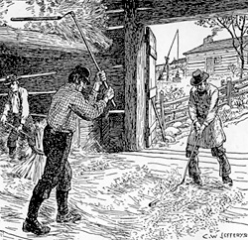

Their main job in the winter was to thresh the grain crop. The workers used a tool called a flail. Two large sticks were held together by a chain. By swinging one stick, the other would strike the pile of grain, separating the edible part of the grain from the inedible chaff which surrounds it. Both would fall to the floor and the grain and the chaff would then have to be separated by some form of winnowing.

The process was labour intensive, especially if there had been a good harvest. It was natural for farmers to seek a cheaper way of carrying out the process.

The first threshing machine was invented in 1784. By 1830, its use was spreading through the country and the machines had reached Kent and the Isle of Thanet. Their use meant that fewer men would be needed and there would be less income for the labourers.

It was a situation that many workers in other industries had experienced during the years of the industrial revolution but, in 1830, it was the agricultural workers who were faced with the loss of their jobs, in particular the threshing of the cereal crops in the winter. They were facing starvation and feeling were running high.

The Riots

The action began in Kent before spreading to other counties. A revolution had broken out in France in July 1830 and it was thought that agitators or agents from France had travelled from France to Kent.

In the main arable counties, threatening letters were sent to farmers, warning of the destruction of their property if they failed to remove the machines or to raise the wages. One of the letters sent to a farmer in Kent read: “The Lane down to your farm is dark. We will light it.”

Another read: “This is to inform you what you have to undergo Gentlemen if providing you don’t pull down your machines and rise the poor mens wages, the married men give two and sixpence a day the single two shillings, or we will burn down your barns and you in them. This is the last notis.” [sic]

Most agricultural workers at the time would have been unable to sign their own name let alone write such threatening letters and the letters are evidence that literate people were involved in the riots. Many of the threatening letters received by farmers in several counties were signed by a mythical ‘Captain Swing’ and the events became known as the ‘Swing Riots’.

The action spread quickly. It was mostly led by local men, known as ‘Captains’, though some men travelled to different areas, inciting riots. Machinery such as that at paper mills and sawmills were destroyed as well as farm machinery. There were arson attacks and riotous assemblies.

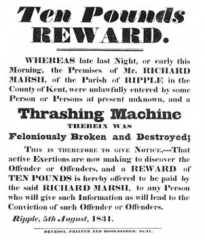

Rewards were offered for information leading to the arrest of the culprits.

A poster was printed:

“A FRIENDLY

CAUTION

TO THE

LABOURERS of KENT.

Fellow Countrymen,

Still almost daily we hear of Breaking Machines, and Burning Stacks of Corn, Barns, &c. Some of you are led to join in these things by persons who are unknown to you; these persons pretend to be your Friends; they only urge you on, they would have you believe, as a means of obtaining increase of Wages and Employ. Be no longer deceived, the day will come when some unexpected intervention of Providence, or the activity of Man, will unmask these wretches, when their dark designs will be discovered to have been, to create Confusion and Disorder, in the hope of benefitting themselves by Plunder, or by over -turning the established Order of Things, and you will find too late, that you have been the Dupes of their designs. If they, through your means ruin the Farmer, it is perfectly clear he cannot employ you, and if you are apprehended for a Breach of the Law, you will be left to suffer, and your leaders will have Cunning enough to keep their own Necks out of the Halter. Now as you cannot be acquainted with the length to which the Arm of the Law can reach you, my friendly object is to open your Eyes, that you may no longer be ignorant of the risk you run. Learn then, that the Law says it is a crime even if a man CONCEAL what he knows in these matters, although he never consented to the commission of the Crime, and that he can only save himself from the consequences, by discovering the Offence to a Magistrate, with all the speed he can. Further the Law says, if a Man, though not present when the Crime is committed, is discovered to have procured, counselled (that is advised,) commanded, or abetted, (that is encouraged, or backed another to commit it,) he is an Accessory before the fact, and equally liable to Punishment. So again if several Persons set out together, or in small Parties, upon one common Design for any Purpose in itself unlawful, and each takes his part: some to commit the Crime, others to watch at proper Distances, and Stations to prevent surprise, or to favor the escape of those who are more immediately engaged in it, they are all (in the Eye of the Law) punishable for it. Follow then the example of those Fellow-Labourers, who have respectfully applied to their Employers for increase of Wages, where they have been too low, and who have obtained Redress. There can be no doubt but those Farmers who have hitherto paid you too little, will now see their Error, and be induced by public Opinion, to follow the Example of those Farmers who pay you what is just for your Labour. Follow this advice, given by a Stranger to you, who has only your, and His Country’s Interest at Heart, (he is no Farmer) turn your backs upon your Enemies and Deceivers, pursue your Honest Industry, and become once more worthy of being respected as MEN OF KENT.

[Signed] The Poor Man’s Friend.

FARMERS,

To such among you as pay inadequate Wages, I say, read attentively the above

Advice and Caution give to your Men, and remember that “The Labourer is

worthy of his Hire.” I do not call upon you to listen to wild and unreasonable

Demands, but I recommend you at least to follow the example of those Farmers,

who deal JUSTLY by their Labourers. Employ THEM instead of using Machines.

This will it may be hoped make them contented and comfortable, and bring them

back to a sense of their Duty.

HAYWARD, PRINTER, AND BOOKBINDER, DEAL.

Perhaps the poster could be described as a laudable attempt to defuse the situation but I wonder how many copies were printed and where it was meant to be displayed. How could illiterate agricultural labourers be expected to read it?

Perhaps it was designed to be read out loud by town criers in the town centres but the people it was designed to influence would not have been there.

The Action in Thanet

The first threshing machine to be destroyed was in Kent on 28th August 1830 and by the third week of October more than 100 machines has been destroyed in East Kent. The action did not spread to Thanet until 6th October when threats were made to destroy machinery at a farm in Margate, though the threats were not carried out.

On the night of 21st November, Thomas and his companions were supposed to have left the pub and walked to Vincent Farm where they broke up the threshing machine. It was said that Thomas had acquired a saw which was used to saw the machine into pieces.

The men were also accused of breaking at least six more machine at different farms spread over quite some distance two nights later. It seems unlikely that they could have covered such distances on foot in one night and, though accused of the crimes, there was no report of evidence that they were involved.

We don’t know if the men had plotted in advance of the events of 21st/22nd November or whether they had made a spur of the moment decision under the influence of drink. And if they had planned their actions, whether they had done so by themselves or whether they were part of a larger co-ordinated group of some 40 to 50 people which began destroying farm machinery across Thanet on that night.

According to reports in the Times, some of those men were in female attire. They were armed with “sticks, axes, saws, hammers and bludgeons” and had their faces blackened.

By 26 November the Kentish Gazette reported that “The Isle of Thanet is now the scene of confusion, agitation and alarm from the nightly appearance of gangs with their faces whitened” (with chalk) “and armed with bludgeons etc”.

Yes, there may have been professional agitators at work, maybe even ones from the French revolution across the channel. And maybe some of the riots took place on Saturday nights after the public houses had closed and those involved had drunk alcohol, but not all of them.

This was no drunken rabble out for a fight. These were normally law abiding and hard working agricultural labourers who had been driven to despair by their working conditions and who wanted nothing more than to earn a decent wage to support themselves and their families. And they were driven to take drastic action.

The Results of the Action

Unlike other places, most of the action in Thanet was directed against the threshing machines and at the larger farmers who paid the low wages and by the end of the year the farmers had agreed to the labourers’ demands to dismantle their machinery and to raise their wages.

A fair wage in Kent was now said to be 12 – 15 shillings a week, though the editor of the Kentish Gazette asked “if men can be found to work for 8 shillings or 9 shillings, what is to prevent farmers employing them?”

The men had achieved their aims but it was at great cost. Across the country 2000 people were brought to trial. 644 were imprisoned and 252 were sentenced to death though only 19 were executed, including a 12 year old boy. The remainder had their sentences commuted to life transportation. 505 were transported to penal colonies in Australia, 7 were fined, one was whipped and 800 were bound over to keep the peace.

In Kent, local justices were sympathetic to the plight of the labourers and initially dealt with them quite leniently but the government protested and punishment became harsher.

In Thanet, although other men were taken up by the police for being involved in the events it seems that only Thomas and his companions were arrested and charged. Evidence was given against them by two of the accused, one of whom had been promised immunity from prosecution. Presumably the other did so in expectation of a lighter sentence for himself.

Under such circumstances, their accounts were not only suspect but they didn’t agree with each other. Only one of the men identified Thomas as present at Vincent Farm and with the saw.

There was no other evidence that Thomas had been seen with a saw at any time or even that he had been present at the breaking of the machine other than the word of a suspect witness.

Circumstantial evidence was that the men, including Thomas, had been drinking and that he had been heard to refer to a threshing machine, which is not surprising given that it was the topic of conversation for farm labourers throughout the country at that time. There was no evidence or proof that Thomas had been one of the men who broke up the machine at Vincent Farm.

Indeed, there is doubt that the men would have been capable of walking of some 5 – 7 miles and breaking the machine in their undisputed drunken state. Would they not have chosen a nearer farm for their action? Could the attack have been made by other people?

Even if Thomas had taken part in other such events during that time, it is doubtful that he was guilty of the actual charge laid against him. Such was the lack of direct evidence and the lack of agreement between the two prosecution witnesses that the trial should have been halted and the charges dismissed.

However, at the Quarter Sessions in Dover on 21 December 1830, Thomas and the other men were convicted of breaking up the threshing machine at Vincent Farm and sentenced to be transported for seven years. They were lucky not to be executed, as happened elsewhere.

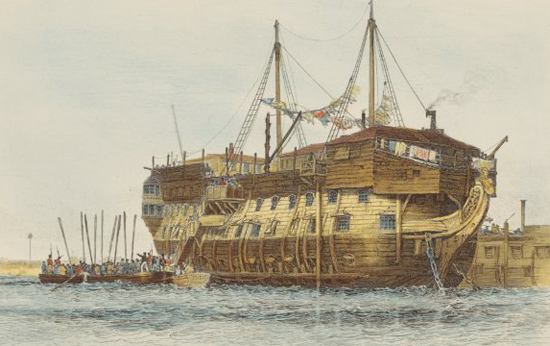

Thomas was taken on board the prison hulk ‘York’ to wait for transfer to the convict ship.

Transportation

On 6th February 1831, Thomas was onboard the convict ship Eliza when it sailed from Portsmouth together with 243 other male convicts. All of them had been convicted of machine breaking or associated crimes in counties across the country.

The ship was bound for Van Diemen’s Land, now known as Tasmania, and arrived there on 29th May with all the convicts having survived the journey (at a time when it was not unusual for there to be deaths during the voyage). On arrival, the convicts were allocated to work for various settlers.

Thomas Hepburn was assigned to the Civil Commandant at Port Dalrymple, Edward Abbott. Formerly a military officer and then Deputy Judge Advocate of the county, when he took up the post of Civil Commandant he was granted 3,210 acres of land and presumably Thomas worked on the land.

Meanwhile, his wife Elizabeth had been receiving outdoor relief for herself and her two children in Acol. When the men became eligible to apply for their families to be brought to Australia at government expense, Elizabeth and the children were able to join Thomas. Over time they had another three children.

Free pardons began to be issued in 1835 and Thomas was one of the recipients. He would have been able to return to England (at his own expense) but he and his wife settled in south Victoria and raised their family there.

Outcome of the Swing Riots

There was strong social, political and agricultural unrest throughout Britain in the 1830s and the Swing Riots were a major influence on the government and proposals for change in parliament.

In 1832, the Representation of the People Act, known as the Reform Act, introduced wide-ranging changes to the electoral system of England and Wales making members of parliament much more representative of the people.

Previously there had been county members who were mainly landowners and borough members who were meant to represent the mercantile and trading needs of the country. In practice, both were open to corruption and, particularly with the county members, gave rich landowners considerable influence over land owning matters which did not represent the needs of the land workers.

In county constituencies the number of voters was greatly increased, with not only rich landowners being eligible to vote but also the owners, long term leaseholders and tenants of smaller amounts of land and farms. At the time, the land had to be worth at least £10 (£8000 at 2007 values).

Whilst the farm workers did not achieve the right to vote for some years, at least from 1832 they were being represented by owners and tenants who knew much more about the needs of small farms and the workers than distant large rich landowners.

In 1834, The Poor Law Amendment Act ended the system of ‘outdoor relief’ by which people had been given food and clothes but no help with keeping a roof over their head. Under the old system, if a worker had moved to a parish to take a job, they were not eligible for the outdoor relief unless they had lived and worked in the parish for a year and a day. A labourer could live in a village for many years and for the most part be gainfully employed but, because none of his jobs had lasted for 366 days, he was not eligible for ‘outdoor relief’ between jobs.

Under the new act, a chain of workhouses was built across the country to supplement the existing ones which only took in the old and infirm who were unable to work. The new workhouses took in the unemployed and set them to work for their keep, growing food for the inmates, working in the laundry, whatever was needed to run the workhouses.

Conditions for rural workers did not improve and agricultural workers continued to suffer as mechanisation increased and jobs became fewer. And so, as we shall see in the stories of other individuals in our family history, the Isle of Thanet Union Workhouse, which was built in 1836 at Minster, was to provide a home and help for several members of the Emptage family who fell on hard times.

They did not know it but they had Thomas Hepburn and his fellow Swing Rioters to thank that such help was available when they needed it.

My hope is that Thomas, his wife Elizabeth (née Emptage) and their five children went on to live good lives in their new country.

Susan Morris

20 May 2013

Notes

As frequently occurred in those days, there were variations in the spelling of Thomas’ surname: Hepburn, Hepborn, Hepbuirn and Heborn.

He was also known as Thomas Winterbourn.

It is from the flailing process that we have the expression ‘to separate the wheat from the chaff’ which is used to mean separating the good from the bad, the best from the least.

In modern farming, the whole process of harvesting, threshing and winnowing is done in the field in one operation by large combine harvesters.

Sources

‘The Isle of Thanet Farming Community’ by RKI Quested

‘Farming Isle’ by Anita and Alan Hardcastle of Thanet Farm Archives

London Illustrated News

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Enclosure_Acts

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Threshing

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Threshing_machine

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Swing_Riots

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Swing_Riots#cite_ref-harrison249_1-0

http://www.genuskent.co.uk/kenthistory.asp

http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/education/politics/g5/

http://www.historyhome.co.uk/peel/poorlaw/plaa.htm

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Reform_Act_1832