Edward was my father, the son of Henry Thomas Emptage and Malbry Jane Wilson. You can read their story here.

Edward and his twin brother Charles Frederick (Charley) were born in East Farleigh, near Maidstone in Kent in 1892. Their sister Ellen (known as Helen) was born in 1894 in Tunbridge Wells and a year later they were in Hammersmith, London where Walter Dansy was born at 7 Felgate Mews.

Following Henry’s death in a workplace accident a year after Walter was born, there was an enormous burden on Malbry to feed and clothe her children: Alfred George (who had been born in Thanington, Kent in 1890) Edward and Charles, Helen and Walter Dansy. The eldest was six and the youngest was just one year old.

The records for 1897 and 1899 show that Alfred, Edward and Charles attended Brook Green school in Hammersmith and Fulham. To us today, it seems odd that even though their father had died in 1896, he was still shown as their parent or guardian rather than Malbry. In June 1897 the family were living at 150 Sulgrave Road but by July 1899, the family was living at 69 Wharton Road, Hammersmith.

Home circumstances for Malbry and the other children must have been very difficult. My father told me they lived in abject poverty and they were often hungry. So it was little wonder that the three youngest sons, Edward, Charles and Walter, found the promise of army life, with travel and three square meals a day, very attractive. By 1909 Edward had enlisted into the Royal Engineers and Charles (Charley) into the “Buffs”.

Military Service

Edward joined the Royal Engineers and became a driver in the A Signal based in Stanhope Lines Aldershot. In those days a driver was a person who took control of a team of horses, not motorised vehicles. During those first few years Edward was sent to different training camps, including Cheriton and Skipton. Edward learnt his skills handling horses, at the same time being taught signal and communications.

By the outbreak of World War One he was a Corporal in the Royal Engineers 4th Signal Company. 4th Signals was one of 7 Signal Companies set up by the Royal Engineers. It was their job to lay telegraph and communication lines prior to battle. His regiment was also part of the Royal Horse Artillery and Edward spent a lot of his time looking after the horses.

Edward was only four when his father died but perhaps he remembered his father working as a furniture remover’s carman, driving the horse and cart. Perhaps he was allowed to help his father look after the horses because there is no doubt that Edward grew up to love horses and so we can understand one story which he told me.

Unknown to many people the Chinese were recruited in those days to look after the horses on the battlefields. They were general workers and were employed so that the soldiers had more time for other duties. Apparently he caught one of the Chinese workers trying to kill a horse by battering him over its head with a heavy stick. These horses if wounded would normally be killed humanely for food. Edward stopped him and nearly beat him to death in his rage at what he was trying to do. No action was ever taken over that due to the circumstances and, of course, in those days a Chinese labourer would have been the absolute dregs within the Army.

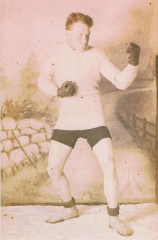

Those early years of hardship had made him a strong, resilient and hard working man and he became an army boxing champion. Through his efforts to do well, he was promoted to Transport Sergeant and was sent with the British Expeditionary Force to France. He was an experienced soldier by the start of WW1 but like every young soldier would have had little idea of the horrors to come.

Thousands of war records were destroyed during the blitz of London in 1940 and it seems Edward’s were amongst them. So, for knowledge of his military service, we must turn to records of the Company’s movements and family stories but Edward was no different to so many men who went through the horror of the war and were reluctant to speak about them their experiences but he did occasionally tell me a story or two.

The early months of the war produced some of the hardest battles ever fought and Edward saw action in Ypres and the Somme. During this time he sustained a bullet wound to his right upper arm. When I was a child he would often tell me when it was going to rain as his arm would start to ache. I never believed him of course but then again it might have had some grain of truth to it.

As a signals expert he and his team of men would have to venture over unknown territory to lay cabling between the battalions so that they could communicate with each other. On one particularly hazardous mission, Edward had to crawl at night time through a field that had seen battle the day before. I remember as a child how he described hiding amongst not only dead soldiers but dead cattle and retrieving signalling equipment with the Germans only yards away. He succeeded in his mission and for bravery was awarded the Belgian Croix de Guerre. Unfortunately, there is no citation available and so we only have the limited details which I remember my father telling me. I think it was during the Battle of the Somme but I can’t be sure.

After the War, Edward transferred to the Army Reserve and spent the next 20 years as a specialist telegraphist and linesman for the General Post Office.

When war broke out in 1939, Edward was too old to go to war but in 1941, at the aged of 49, he was given command of the 25th (36th GPO) East Kent Home Guard and the rank of Major. When I am feeling down at any time I picture my father as a Captain Mainwaring in Dads Army and have a chuckle to myself.

Marriage and children

In 1917 Edward had married Jessica Emily Simmons and after the war they had two children, but sadly the baby girl died aged just one month. They divorced and Edward married my mother, Eileen Smith nee Morris in 1949. Edward died in 1966, aged 74.

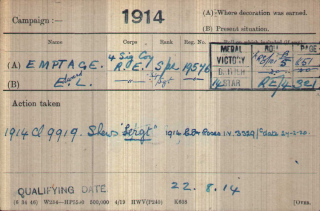

Edward Lindsey Emptage: Regimental No. 19576, Transport Sergeant 4th Signal Company Royal Engineers.

Medals The 1914 Star with Clasp and Roses,Belgian, the British War Medal, the Victory Medal and the Croix de Geurre by the Belgian government.

Company Commander 25th (36th GPO) Battalion Kent Home Guard 1941-1944, awarded the Defence Medal for WW2.

My father had survived WW1 but at what cost? How did all these horrors of WW1 affect our fathers and grandfathers?

It is hard for us to imagine what it must have been like to be stuck in a field trench and being bombarded day and night. The noise of exploding shells and whistling shrapnel must have been appalling. The experience or fear of being gassed. It must have made them different from people who were fortunate enough to escape it all.

My father was nearly 52 when I came into this world and by the time I was 10, he seemed to me to be very old. So we had a two generation gap between us which kept us apart. I only knew him as a hard working, stern and extremely tough man who cared for his family, but did not have the ability to show love or affection. It was if he never wanted to be caught off guard, and I co-existed with him for seventeen years before leaving home, but in all honesty I never ever really knew him.

As the son of Edward who has never been near a war and has not had to endure what he did, I would like to take this opportunity to say a heartfelt thank you and if we never did really see eye to eye when I was growing up I can now, for the first time in my life understand why. Thanks Dad and thank you Charley and Walter for helping make this country a safe and democratic place that it is today.

David Lindsey Emptage

4 May 2015