James William Emptage was my grandfather and Stanley was his son, my father. Neither of them had siblings so I grew up without any Emptage aunts, uncles or cousins.

Stanley had lost contact with his father in the 1930s and, believing him to be deceased, declared him as such in 1943 on his marriage certificate but in reality James did not die until 1953 as enquiries in the 1980s proved.

What had caused Stanley and James to lose contact with each other? Why did Stanley think that his father had died?

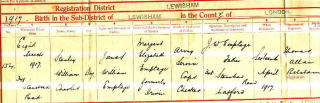

James was born in Gillingham, Kent in 1883, the only child of Stephen William Emptage and his wife Harriet (Cane). Stephen was a foreman-carpenter in Woolwich Arsenal and his father, John, was a mariner, working for the War Department at the time of Stephen’s marriage. James married a dressmaker, Margaret Irwin in 1912 and was 34 when his son Stanley was born in Catford, south east London in 1917.

James served in the first world war but it seems his service records were amongst those destroyed by fire during a German bombing raid on London in 1940. However, we know that he served with the Army Service Corps on board the Caroline Class Cruiser HMS Cleopatra.

HMS Cleopatra was commissioned into the Royal Navy in June 1915 and formed part of the Harwich based force operating in the North Sea to guard the eastern approaches to the English Channel. She took part in several engagements with the enemy, sustaining damage in the process but always managing to return to base to be repaired and to return to the action. It was during one such operation that James suffered a head injury which led to him developing epileptic seizures.

Following the war, James joined the Metropolitan Police but in 1924 he had a seizure at home and fell, with his face coming into contact with the grate of an open fire. His face was badly burned and he spent time receiving treatment in hospital in Edmonton.

Two years later Margaret sadly succumbed to tuberculosis and died. Because of his epilepsy, James was unable to look after his eight year old son and Stanley was placed in a Shaftesbury Home by Lewisham London Borough Council (named after one of the home’s benefactors, the great philanthropist, the Earl of Shaftesbury).

It was originally a Boys’ Industrial Home set up in 1881 for the reception and industrial training of destitute boys. The committee offered places to children whom they knew to be destitute or were the children of poverty-stricken parents. Boys were rescued from the perils of the street, fed, clothed, housed and educated at a local school. The older boys were taught shoe mending and the younger boys made bundles of firewood to sell. The aim was to start them in life with a fair prospect of doing well.

Sadly, Stanley was not the only Emptage to find himself in such a home/school. History doesn’t tell us what life was like for Alfred George Emptage, aged 11 at his school in Macclesfield in 1901 (where he was being taught to mend shoes) but we know that Stanley spent two unhappy years at the Shaftesbury Home.

By 1926 the home was being run on very hard lines. If just one boy transgressed, physical punishments were given to all boys. Thankfully Stanley still had contact with an aunt, his mother’s sister. In 1929 she found him to be suffering from both malnutrition and the effects of the harsh regime. She raised the alarm and, in co-operation with the local authority, she removed him from the Shaftesbury Home.

Stanley’s aunt wasn’t able to offer him a place in her own home but arrangements for Stanley were made through the Metropolitan Asylums Board which placed Stanley on board TS Exmouth, a training ship moored in the Thames estuary, off Grays in Essex.

The MAB had first come into being in 1867 following review and criticism of the workhouse system, which needed to provide not just for the sick and elderly but for children and able bodied adults as well (whilst also doing what it could to deter those able bodied adults from seeking help and thus becoming a charge upon meagre resources). Florence Nightingale was one of those who argued for the provision of trained nursing care, medication and facilities for London’s poor people suffering from infectious diseases or insanity. Smallpox and fever hospitals were built and lunatic asylums were opened.

The MAB, which also cared for pauper children, had taken over the management of the Training Ship Exmouth. As detailed on The Workhouse, the ship was able to take 500 boys who would otherwise be a charge against the parishes’ poor law rates and train them in the art of seamanship, for service in the Royal or Merchant Navy.

“Boys were able to join the ship from the age of twelve. Their first task was to learn how to mend and patch their own clothes. They also had to learn how to wash their clothes, and keep their lockers and contents in good order. Each boy had his own hammock which was stowed during the day, leaving the decks clear of bedding. As well as learning the skills of sailing, rowing, sail and rope-making, gunnery, and signalling, they continued ordinary school work, and other physical activities such as swimming and gymnastics. The ship had its own band and bugle-band.”

The website has photos of the ship and, dated 1929, the boys at drill and some evidently happy boys enjoying eating a snack. For Stanley, it must have a been a world away from the harsh regime he experienced in the Shaftesbury Home and he remained there for four years until 1933, achieving the rank of boy CPO.

As well as developing seamanship skills, Stanley developed his love of music and his music abilities and became an excellent cornet player. News of his prowess reached the South Staffordshire Regiment then based in Aldershot. Stanley was invited to a ‘cream-tea’ during which he was offered an army career as a bandsman with the promise of being sent to the Royal Military College of Music at Kneller Hall in Twickenham.

It was an offer Stanley couldn’t refuse and he joined the regiment as a boy soldier that same year. Through the mid 1930s, whilst in barracks at North Camp, Aldershot, he received birthday cards from his father but after a few years they abruptly stopped.

In September 1938 he began a two-year course at Kneller Hall but the outbreak of war a year later prevented him from continuing. Had he completed the course successfully he would have qualified as a bandmaster which was warrant officer rank, although he would have had to wait until the age of twenty-five to take up the position.

During the war, Stanley was posted to Whittington Barracks in Staffordshire, where he met Marjorie Southam. They married in 1943 and I was born in 1944. Not long after my birth Stanley was visited in Whittington Barracks by two officials who asked him whether he could contribute to his father’s upkeep in Claybury Hospital, Ilford. He told them he could not as he had no money and he was now married and had a son. They left and he heard no more about the matter.

Claybury Hospital was a large London County Council mental hospital housing, at its peak, some 3,500 psychiatric patients, doctors and nurses. It was a ground breaking establishment which had become world renowned for the treatment of mental disease.

It would seem highly likely that effects of James’ war time head injury and his epilepsy had worsened to the point that he was no longer able to look after himself. James would have been admitted to the hospital as a pauper, with the costs to be paid by his local authority. Prior to the inception of the National Health Service, the local authority would have attempted to recover those costs from the patient’s family, as happened when the two officials visited Stanley in barracks.

[It was not until the mid-1980s that Stanley discovered from official records that his father had died in 1953. His cousin Norah later told him that his father had been given a pauper’s burial.]

After the war Stanley left the army and settled down to dance band work until the pop era established itself. My mother had attended secretarial college after leaving grammar school and acted as his secretary. They secured band work for consecutive seasons in Exmouth during the summers of 1947 and 1948.

In 1949 the summer season was spent in Margate. In those days there were many more small individual retailers represented on the High Street than are seen today. My father told me there were a goodly number of small shops in Margate with the name Emptage above the window. Thanet and the surname Emptage seemed to be inextricably linked.

Roger Mainwaring Emptage

with additional research by Susan Morris

20 October 2015

Susan writes:

It is clear is that the Shaftesbury Home failed to live up to the expectations of its benefactors and, in so doing, failed the boys in their charge. But it is also clear that when Stanley was transferred to the TS Exmouth, he availed himself of every opportunity offered, including developing his music skills. I smiled when reading Roger’s description of the ‘cream tea’ which the army used to head hunt Stanley, thus depriving the navy of his service.

It is hard to imagine what would have happened to Stanley had the Metropolitan Asylums Board not existed to rescue destitute boys from the street and train them for future service. That the training took place without the need for a harsh regime is clear from the happy faces in the 1929 photo of the boys on board TS Exmouth.

It seems clear that Stanley fully lived up to the MAB’s expectations and repaid them in full for whatever it cost the board to keep, educate and train him, to enable him to live a good productive life.

Sources

HMS Cleopatra:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/HMS_Cleopatra_%281915%29

Shaftesbury Homes: http://www.childrenshomes.org.uk/SH/

Metropolitan Asylums Board: http://www.workhouses.org.uk/MAB/

Training Ship Exmouth: http://www.childrenshomes.org.uk/TSExmouth/

Claybury Hospital:

http://thetimechamber.co.uk/beta/sites/asylums/london-county-asylum-claybury

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Claybury_Hospital

http://ezitis.myzen.co.uk/claybury.html

Images

The photograph of the boys at drill on The Exmouth was used with permission from Peter Higginbotham, owner of The Workhouse website.

All other photographs provided by Roger Emptage from the family album.