In December 1956 and Jan 1957 my mother was in hospital. There was nobody who could look after my brother John and me for two months so there was no choice but for us to go into a children’s home. The local authorities wanted to split us up and our father fought to find a home which could or would take both of us, for which I have always been so very glad.

At that time we lived in Greenford, Middlesex and the home was at Herne Bay, in Kent. In a straight line, the distance is about 70 miles but with Greenford being north of London and Herne Bay being on the Kent coast, in reality the distance was longer. Even today, by the motorways, the journey would take two hours each way, skirting London, but there were no motorways then and our father would have driven through London and across the Thames.

Few people had cars in those days but our father was a sales representative and had a company car so he was able to visit us. However, it was at the time of the Suez Crisis and there was petrol rationing so his visits were limited to just once a week.

December and January weren’t the best months to be walking along the prom on cold windy Sundays and then sitting in the one cafe which was open and eating ice cream but I remember my brother enjoying large knickerbocker glories.

For December we were in a part of the children’s home which was in a tall terraced house right on the sea front. It was run by a young couple, with the man working as the projectionist at the local cinema. They tried to make the atmosphere as homely as possible. I remember an enormous Christmas tree in the bay window and there was a playroom in the basement.

My brother was five and I was eight so both of us had to go to school, which was quite a walk. I remember taking John to church on Sunday and feeding him sweets to keep him quiet.

We had an occasional visitor apart from our father. Our aunt Joan and uncle Ernest (Ernie) lived in Canterbury. Joan and my mother Eileen were the two oldest of the twelve children born to Walter Dansy and Emily Sophia Emptage in Canterbury between 1920 and 1939.

It’s less than 10 miles from Canterbury to Herne Bay. Ernie was a delivery man and had the use of a van, so he would call to see us whilst out on his rounds. I’m wondering now if it was he who knew of the children’s home in Herne Bay and suggested it to our parents.

In January the number of children had fallen and we were moved to the main part of the children’s home, say half a mile away, up on the cliffs. It was a large house overlooking the downs and the sea but it was run far more formally. Memories of our time there are not so good.

I have no idea why the other children were there. Family breakups? Orphans? What I did know, and kept very firmly in my mind, was that our time there was limited. We would be going home, soon.

My brother and I have mixed memories of those two months but, most importantly, we did go home, to loving parents. As I have discovered recently, other Emptage descendants were not so fortunate.

In the late 1980s, a social worker, Margaret Humphreys, began to expose the horror and scandal of child migration.

Child migration began as far back as 1618 when a hundred children were sent from London to the Virginia Colony (which was to become one of the states in the USA). It continued in the 18th century when many children, especially from Scotland, were sent by merchants and magistrates to the colonies in the Americas. It continued until the practice was exposed in 1757.

However, in the 1830s, in an effort to suppress juvenile vagrancy, children were sent to the Cape Colony in South Africa, to the swan River Colony in Australia, and to Toronto and New Brunswick in Canada. The instigators of the scheme acted through altruistic motives. They were appalled at the conditions that children were working in and believed that the children would have much better lives in the new countries, in lands of opportunity.

A formal child migration scheme was founded in 1869. Although largely discontinued by the 1930s the practice continued through to 1970 when the last group was sent to Australia. In 100 years, some 130,000 children were sent to Canada, Australia, New Zealand and Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe). There were mixed motives but overall there was a sustained effort to increase the population and skills in these still new countries.

Specialist agencies sent the children abroad, many supplied by respected national charities such as Barnados. Churches including the Church of England, the Methodist Church, the Salvation Army and the Catholic Church all played major roles.

Children were sent from orphanages and workhouses. Promised that they were going to the ‘land of milk and honey’ in reality the children often found themselves in harsh living conditions, maybe working in institutions, including religious ones.

Boy ploughing at Dr Barnardo’s Industrial

Farm in 1900, reproduced on a Canadian

postage stamp in 2020 to commemorate

Home Children emigration

They’d work on the institution’s farm or be employed in building, whilst hungry and sometimes without basic clothes and shoes. Depending on the country some were sent to remote farms where they would be treated as little more than slaves. In many cases the children had no documentation, no birth certificates.

According to the British House of Commons Child Migrant’s Trust Report, “It is estimated that some 150,000 children were dispatched over a period of 350 years — the earliest recorded child migrants left Britain for the Virginia Colony in 1618, and the process did not finally end until the late 1960s.”

Although it was widely believed by contemporaries that all of these children were orphans, in fact many children were sent who had parents and other family members. Children who, like my brother and I, had been taken into care for various reasons but who, unlike John and I, were never returned to their parents or families.

Indeed, parents who tried to reclaim their children after the family circumstances improved were told that the child had been fostered or adopted and that it would be too upsetting for the child to be disrupted again. Letters written by the parents to the child via the children’s homes were not passed on. And in some cases the child was told that their parents didn’t want them any more, even though the parents had tried to get in to the building to see them. Some children were told that their parents were dead and that they were being sent to somewhere that they would have a better life. There were few subsequent checks on the conditions in which the children found themselves.

Since 1987, Margaret Humphreys has worked to reunite these children with their families. Many of them would be in their 40s, 50s or 60s, perhaps older. Perhaps too late for their parents but maybe not too late to connect with their siblings back in Britain. She worked to give them the identity that they never had. To give them a sense of their roots.

Even reading heart rending accounts by the child migrants it is impossible to imagine how life would have been for these children growing up with memories of life in Britain fading and with no knowledge of their families. No knowledge of their roots.

To know that the forced migration of children was still going on in the 1950s, at the same time as John and I spent two months in care, in that children’s home in Herne Bay, makes me realise just how lucky we were.

But at least three other Emptage descendant children were not so lucky.

The Canadian government website for Library and Archives has an article about the Home Children. “Between 1869 and the late 1930s, over 100,000 juvenile migrants were sent to Canada from the British Isles during the child emigration movement. Motivated by social and economic forces, churches and philanthropic organizations sent orphaned, abandoned and pauper children to Canada. Many believed that these children would have a better chance for a healthy, moral life in rural Canada, where families welcomed them as a source of cheap farm labour and domestic help.”

Although many of the children were poorly treated, others did experience a better life than they would have done if they had remained in the slum from which they were taken, but at what cost? As we know, many of the children were not actually orphans or abandoned but were removed from their families.

The website has a searchable database of the Home Children Records and here we find the names of three Emptage children: George, Emma Jane and Sidney Anderson.

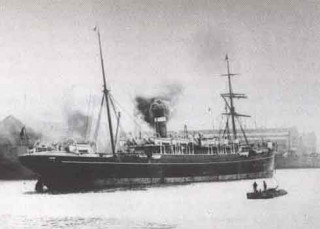

George Emptage was 13 when he arrived in Canada aboard the SS Polynesian in 1888. He left Liverpool on 29 March and arrived in Halifax, Nova Scotia, on 10 April. He was one of a party of 205 males and was sent by Dr Barnado.

I already knew about George as he was the son of my 2 x greatgrandparents, Alfred and Ann Emptage. Alfred had died in 1875, when George was just eight weeks old. Ann had died in 1882, when George was seven years old. Starting in 1882, one by one his older siblings either emigrated to the USA, left Thanet or died, leaving just one brother in Margate, 11 years older than George.

We don’t know whether his brother William was unable to provide a home for him or whether George wanted to emigrate and join his brother and sister in New York. According to the Canadian database, George’s name was on a list of the children from workhouses sent out to Canada in 1888 by Dr Barnado. The reference is to the Department of Agriculture so it is thought that he was sent to work on a farm.

The Canadian 1891 Census shows that George, then aged 16, was working as a domestic assistant with a family in Tiverton, Ontario. By 1900 George was an insurance agent in Missouri, USA, working for the same company as his brother Alfred and sister Rose.

So clearly George had been able to make contact with Alfred and clearly George was one of the lucky migrant children.

Emma Jane Emptage was 11 when she arrived on the SS Mongolian in 1893 from Liverpool. Born in 1882 she was the youngest of ten children born to Joseph Henry and Sarah Ann Jones of Margate. Joseph had died in 1887 and Sara in 1891. By 1893 at least five of Emma’s siblings had died in infancy and another died aged 25 in 1893. The last record for her oldest sibling, Ellen, was the 1881 census when she was a general house servant in Margate. We have no idea what happened to her.

Apart from Ellen, by 1893 there were just two remaining siblings, Kate who was 7 years older than Emma and Frederick who was only 4 years older than Emma. Clearly neither of them were of an age to look after Emma and presumably none of her aunts and uncles were able to offer her home. There’s nothing to say what happened to her. Was Emma placed in the Thanet workhouse and then referred to the migrant scheme?

On arrival in Canada Emma was sent to the Maria Rye Homes at Niagara-on-the-Lake, Ontario. Maria Rye was one of the social reformers from England who thought that the children would have a better life in Canada. An official report in 1875 by an inspector on behalf of England’s local government board had been highly critical of the process of immigration of children into Canada. Following the release of the report, Maria Rye, who was one of the subjects of the report, stopped bringing children into Canada for a few years. We can only hope that, by the time Emma arrived there, the conditions had significantly improved.

In 1899 Emma, aged 17, married Thomas Cathcart in Simcoe, Ontario. They lived in Canada and had eight children. Her husband died after 37 years of marriage so Emma was widowed when she was 55. We don’t have any further information about Emma.

Sidney Anderson Emptage was 15 when he arrived in Canada on the RMS Cedric from Liverpool in 1929. He was sent by the National Children’s Home and only his name appears on the list, no other details apart from his birth date in 1913.

Although he was listed as Sidney Anderson Emptage, I think it was actually Sidney Atkinson, born in Grimsby. His father was Richard John Emptage and his mother was Lucy Ann Atkinson. Richard died in 1917 and Lucy in 1921.

Sidney was the youngest of 7 children. Three sisters had died when they were 22, 16 and 14. His oldest surviving sibling was just 16. Clearly she was not able to look after him as well as her other two brothers. Their mother died in April 1921 and the 1921 census was taken on 19 June 1921. We will have to wait until January 2022 before we can view the 1921 census to see if it offers a clue as to what happened to Lucy’s children in the immediate aftermath of her death.

Having arrived in Halifax, Nova Scotia in 1929, Sidney was sent to the National Children’s Home in the port city of Hamilton on the west side of Lake Ontario. It is doubtful if he stayed there very long as he was already 15. I assume that the children’s home helped him find a job. We know nothing more about him until he appears on the 1949 electoral roll in Hamilton with his wife. By 1853 he was a manager in Hamilton. And in 1954, as a sergeant major, aged 41, in the Battalion of the Royal Canadian Artillery he received a citation.

Sidney remained living in Hamilton and died in 2005 aged 92, just a few days after the death of his wife. We only have the electoral rolls to go by and have no record of any children but we have no records between 1929 and 1949 so it is possible that they did have children.

George, Emma and Sidney, three Emptage orphans from three different families, all migrant children. I hope and trust that, even if their early lives were hard when they were orphaned and their beginnings in Canada were difficult, they went on to live happy and fulfilled lives.

It is possible that other Emptage children were migrated, to Australia, New Zealand or Rhodesia but I have not found a central source in those countries to be able to identify them. I would like to hear from anybody who knows of any other Emptage migrant children or of such a research source.

I know that most of the migrant children were not told where they were going. Indeed some thought they were going on a day trip or a short holiday and weren’t told their destination until they were on board ship. And then they were told that they were going to a new life, a better life. Of course, they had no idea how far away Australia or Canada were. Or that they were never see their families again.

I look at the images of children on board ship heading for these countries and they look so happy, believing they were going to a new life, a better life, and my heart breaks knowing the reality that they were actually going to experience once they stepped ashore.

One of my favourite writers of genealogical fiction, M J Lee, has written on the subject. His book The Vanished Child concerns the efforts of genealogist Jayne Sinclair to find the child. Exceedingly well researched, it tells the story of a young boy who was sent to Australia under the migration scheme. I wholeheartedly recommend the book for a glimpse of what might have lead to a child being put into care and what life was like for the migrant children. It is available on Amazon as paperback or Kindle edition. When I read the book I did not expect to be writing about the subject just a few months later.

The 2010 film Oranges and Sunshine is based on Margaret Humphrey’s book Empty Cradles which was published in 1994. The title is taken from what the children were told on board the ship bound for Australia; they were going to the land of oranges and sunshine. Instead they got hard labour and a life in institutions with many experiencing abuse and rape.

Sources:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Margaret_Humphreys

https://www.childmigrantstrust.com/

https://www.bac-lac.gc.ca/eng/discover/immigration/immigration-records/home-children-1869-1930/Pages/home-children.aspx.

https://www.bac-lac.gc.ca/eng/discover/immigration/immigration-records/home-children-1869-1930/immigration-records/Pages/list.aspx?Surname=Emptage&

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/magazine-34656346

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-45340295

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Home_Children

https://canadianbritishhomechildren.weebly.com/maria-rye-niagara-on-the-lake.html

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Oranges_and_Sunshine

https://www.dailymail.co.uk/femail/article-1238063/It-happened-I-sent-Australia-child-migrant.html

http://otoweb.cloudapp.net/voyage/