In the early hours of 2 December 1897, the Persian Empire collided with the West Hartlepool Steamship Carlisle City in Margate Bay. In distress, the crew fired their flares at 5a.m. And thus a tragedy began to unfold.

The surfboat Friends to all Nations, powered by oar and sail, was launched with a crew of thirteen, including a medic aid, to attempt a rescue in hazardous conditions. The conditions were such that the surfboat capsized and nine lifeboatmen perished.

The lifeboat Quiver was also launched with coxswain Albert John Emptage at the helm and through almost impossible odds the men succeeded in rescuing the stricken seamen on the Persian Empire and safely brought them back to shore.

According to the Board of Trade Report, the Quiver had taken a route “a little farther out and experienced nothing remarkable on passing the Nayland Rocks and her crew were in ignorance as to the disaster to the surf-boat until they put into Folkestone several hours later.”

The disaster, the inquest on the lifeboatmen and the Board of Trade inquiry were widely reported in newspapers throughout the country. Piecing together the various newspaper reports gives us a full picture of the boat and the event which caused the loss of nine lives.

The Friend of All Nations was a double-headed whale boat, 32 feet long and, in the broadest part, only 5ft 3 inches wide, just enough to seat two rowers side by side. It was built at Cowes in 1878 at a cost of £400 raised by local boatmen and the public.

The boat was run as a co-operative, owned by some 120 boatmen who had to satisfy the management committee as to their competency and who paid a small subscription to entitle them to use the boat and to receive a payment from any salvage.

The first thirteen men who arrived at the boat after an alarm would form the crew and were the ones who decided whether it was safe to go out. The most competent man present was chosen coxswain and was responsible for the boat.

The Inquest

The inquest on the bodies of the nine men who were drowned by the capsizing of the surfboat Friend to All Nations took place in Margate on 3 December 1897. All nine bodies had been recovered and identified with evidence of the finding of the bodies given.

Their names were: Charles Edward Troughton, aged 40, Henry Richard Brockman, 50, John Benjamin Dike, 41, George William Ladd, 38, Edward Robert Crunder, 31, Robert Ernest Cook, 26, William Philpott Cook, 54, William Richard Gill, 35 and William Philpott Cook jun, aged 28.

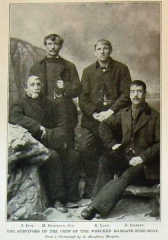

The four survivors were Robert Ladd, Harry Brockman jun, 26, John James Gilbert 20, and Joe Epps. Each gave evidence, stating that they left the harbour about 5.30 am and crossed the bay sailing close to the north wind, so as to reach their object on the second tack. The storm sail was up but the sheet was not fastened, being held by a half turn round the pump and could easily be let go.

A tremendous sea struck the boat when near Nayland Rock and she at once capsized in about twelve feet of water, about a quarter of a mile from the shore. All aboard were thrown into the water.

Robert Ladd said he did not know if anyone was in charge of the halyards, but someone was as a rule and he was sure they would have run. There was not sufficient wind to have capsized the boat if the sheet had been fastened. Harry Brockman thought that the sea was sufficient to capsize the boat even if she had no sail up. It was not, he explained, an ordinary sea but a long curling sea that struck the boat.

When the boat capsized, Robert Ladd felt himself in the sails and heard the mast break. He got clear and then seized hold of the boat. He saw Harry Brockman on the other side. The boat drifted into the bay near the Royal Crescent. Robert Ladd said that he had been going in the boat for the past ten years and the vessel had never turned over before.

Harry Brockman said that about ten minutes after leaving the harbour, when they got to the spit of the Nayland, the sea ran up to them and thinking that it was about to swamp them, he seized hold of the side, but the boat turned over and he felt he was underneath. He managed to get clear and then hung on to the capsized craft.

John James Gilbert, aged 20, stated that he had been out in the Friend of All Nations in worse weather than they had experienced the previous day. He was on the port bow and when they were off the Nayland he suddenly found himself in the water. He was under the boat but diving down he got clear and then, seizing the overturned boat, he clung to it for twenty minutes until he found himself near to the the Royal Crescent seawall.

Joe Epps, said that he did not see the big sea which overwhelmed them. The sheet was never fastened but always held by a half turn round a pump and if it were struck by a sea it would be forced out of the man’s hand.

The craft was the property of the boatmen and Harry Brockman said that theirs was a good boat but that personally he preferred the [Lifeboat] Institution boat, the Quiver, as it was better adapted for bad weather.

Generally they did not wear lifebelts, although they were supplied, as they found the lifebelts to be in the way on top of the heavy clothing which all the crew wore. The lifebelts were more cumbersome in the surfboat than in the Quiver and the crew could not row in them.

A regulation of the National Lifeboat Institution was that all men proceeding to sea in the institution’s boats must wear lifebelts. However, as the surfboat belonged to the boatmen, the wearing of lifebelts was entirely optional although Harry Brockman said that in the present case, belts would have been useful and would, in all probability, have prevented so great a loss of life. But he felt that had he worn one, he would probably have lost his life when the boat turned over on him.

Epps had been underneath the boat the whole time and was barely alive when he was found. He said that he didn’t care for the lifebelts and never wore them and that had he done so the previous day, he must have been drowned.

Albert Emptage attended the inquest and stated that the surfboat Friends to all Nations in whom he had been out many times in, was a good boat, and would not have hesitated to have gone out in her if he hadn’t been the coxswain of the Quiver.

The coroner pointed out that the sad event was a pure accident and the jury returned a verdict of Accidental Death and asked the coroner to convey their deep sympathy to the relatives and friends of the deceased.

The Funeral

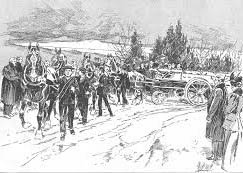

Some 3,000 people, dressed in black, were estimated to have lined the entire route from the Parade to the Cemetery, and places of business were closed from noon to four o’clock. Blinds were drawn in houses and church bells tolled. Much of East Kent was said to be in mourning.

Charles Troughton was the chief cashier of the Lloyds Bank but was also the boat’s medical aid, being the superintendent of the Margate Ambulance Corps. His body was conveyed on the ambulance carriage, supported on either side by local medical men who carried wreaths and followed by his Lloyds Bank colleagues.

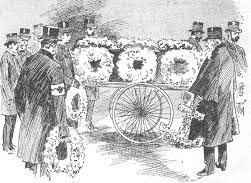

The remains of the eight boatmen were carried on the trolley of the surfboat and were covered with flowers and the Union Jack. They were attended by the four survivors.

The Mayor and Corporation, the Freemasons and Friendly Societies, mounted police, postmen, railwaymen, coast-guardsmen, and firemen of the district attended.

The coxswain and crew of the lifeboat Quiver were also present, with boatmen from Deal, Ramsgate and Broadstairs. The Royal Lifeboat Institution was represented by Commander Thomas Holmes and Mr. Jephcott, the local agent.

The procession made its way to St John’s church. On arrival, the coffins were transferred to the shoulders of willing pall bearers.

The choir and clergy were waiting at the west gate and as the cortege entered the building the organ pealed forth the well known hymn ‘Brief life is here our portion.”

The coffin of Mr Troughton was placed on two tall trestles between the choir stalls in the chancel and those of his companions lined up, one behind the other, along the central aisle.

The service was a united one, with vicars and ministers from several local churches taking part in the readings, prayers and announcements of hymns.

The passage of scripture was from Corinthians xv, the Psalm “God is our refuge and our strength”. The hymns “A few more years shall roll” and “Jesu, lover of my Soul” were also impressively rendered, and to the singing of the latter beautiful lines, the dead were removed from the building.

The procession reformed and moved on to the cemetery.

The image shows the coffins of the eight boatmen, carried on the trolley of the surfboat.

The Thanet Advertiser of 11 December 1897 reported:

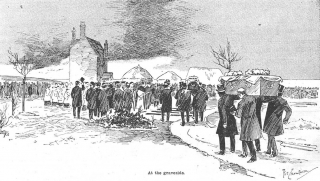

The closing chapter of the ceremony was, perhaps the most impressive of all. The white surpliced choir from Holy Trinity and St Barnabas, with the clergy, met the procession at the cemetery gates, and when the coffin had been again entrusted to the chosen bearers, preceded them to the place of burial, singing meanwhile, “O God our help in ages past.”

With admirable organization, those who followed were ranged in a solid square four deep round the grave, the mayor and corporation, the ambulance delegates, the mourners, and a few other privileged persons taking up a position in the centre.

As at the Church, the service was unsectarian in character, being taken part in respectively by the Reverends, Ashton-Gwatkin (Vicar of St John’s), John James (Congregational Minister), Rev. Taylor Jones, Rev. Lyne (Vicar of St Saviour’s Westgate), Rev. Senior (Holy Trinity), and the Rev. A. Brice (Wesleyan), the Benediction by the Vicar of St John’s.

The formation of the square was well sustained with one exception, when the coffins were being lowered beneath the surface, but a few words from the stewards soon restored its order.

One or two incidents of a peculiarly painful nature were witnessed as the bereaved were taking their last and long farewell of the mortal remains of their loved ones, one elderly lady, in particular having to be led away by kindly friends in a state of utter prostration.

When the mourners and the choir and clergy had gone, those forming the square filed past the graves in line, and so out of the grounds of the cemetery.

Fortunately, the weather, though cloudy, remained fine throughout the afternoon, enabling the many sided arrangements to be carried through as originally intended and without interruption.”

The Board of Trade Inquiry

The inquiry took place on the 22 and 23 December 1897.

Witness after witness spoke in high terms of the seaworthiness of the boat, which was well equipped. Albert Emptage, coxswain to the Quiver lifeboat, said he had been out in the surf boat repeatedly. He always found her a good boat. He said that a tremendous sea was running on the day of the disaster but he would not have hesitated to go out in the surf boat, the coxswain of which was an able man.

The survivors reported that the weather was squally and a heavy sea was running at the time of the accident. When off the Nayland Rock a heavy sea caught the boat, throwing her on her beam ends and before she could recover a second sea struck her, turning her over. But they also said that they had been out previously in much worse seas.

The Inspector said he had examined the boat. He recommended the use of outside hand lines and hand holes on the lower as well as the upper streak. The hand holes were in the worst possible position when the boat was upside down. He also recommended keel hand lines.

The Board of Trade and Inspector were thanked on behalf of the boatmen and the inquiry closed.

The subsequent report was written by Charles P Wilson, the Principal Officer and Assistant Secretary, Marine Department, Board of Trade.

Details of the construction and design of the boat were given and it was written that “the boat was no doubt a powerful boat under either sail or oars when the weather is not too severe for a boat of her size”.

Since it was bought in 1878 it had been maintained in an excellent state of efficiency, both as regards hull and equipment.

The report said that factors contributing to the disaster included that the boat was not self righting and that its very design, which made it an excellent surfboat which would float and support its crew when filled with water, meant that all of the advantages of the boat were reversed if she capsized. The boat would float very high and be out of the reach of the men in the water who were weighed down by oil clothing and sea boots. There was very little for them to reach and hold on to.

“A lifeline is fitted fore and aft in the centre line of the boat for the crew to hold on to and to prevent their being washed out of the boat by the sea, but the usual gunwale lifelines are not fitted.”

“The boat carried two lifebuoys, and it is in evidence that they were on board at the time of the disaster.”

As regards lifebelts, though they were hung on the walls of the boathouse in readiness, the men considered them too cumbersome; they could not use the oars or move about freely with them on, which the inquiry found to be true on inspection. One of the boatmen declared that they were actually safer without them.

The report asked why more men were not saved “in an accident that happened so close to the shore, and when clinging to the boat for a comparatively short time would have saved their lives?”

And went on to say there can be no doubt that the loss of life was due to the fact that efficient means for holding on to the boat when bottom up were not available. An explanation was given of how the three survivors who had managed to cling to the boat had done so through means not designed for that purpose.

The report made suggestions as to what could be done to provide handholds, that gunwale lifelines should be fitted and a keel lifeline should be provided.

The concluding paragraph reads:

There can be little doubt that the Margate boatmen are a bold and adventurous race, who think little of the dangers of the sea when afloat; but I fear that so long as they use a boat such as the Friend to All Nations it will be hopeless to expect them to wear lifebelts, however much it maybe desired”.

The additional comment, though true, seems a little harsh given that, due to the boatmen’s zeal and ability, they preferred to go without lifebelts rather than impede their rowing and therefore the rescue attempt. And it seems to contradict the fact that the loss of life was due to the lack of efficient means to hold on to the boat and ignore the fact that those survivors who were initially under the boat, one of whom remained trapped, would probably have died had they been wearing lifebelts.

The Fund

The Daily Telegraph started a national fund for the benefit of the families of those who had died and a considerable sum was raised. Queen Victoria became a patron and donated £35. By 6 January 1898 the fund stood at £1,372 13s 9d.

If invested, the money, nearly £125,000 at today’s value, would have provided a regular income for the wives and children of those who had died. However, the money did not reach the families.

A Wikipedia article says that the money was mis-appropriated into the management of an Executive Committee of local dignitaries and councillors of the Margate Corporation.

A proposal was said to have been made to build a row of almshouses, which would house the bereaved and also act as a monument to the disaster.

However this was rejected and the committee decided to erect a very large and ornate monument in the cemetery, carved from Italian marble. The memorial reads:

“IN MEMORY OF NINE HEROIC MEN WHO LOST THEIR LIVES BY THE CAPSIZING OF THE MARGATE SURF BOAT “FRIEND TO ALL NATIONS” IN ATTEMPTING TO ASSIST A VESSEL IN DISTRESS AT SEA 2ND DECEMBER 1897.”

It is surrounded by a square white marble kerb with eight tablets bearing the names of the crewmen and the name of the medic aid engraved on the centre front of the kerb.

A statue of a sailor in thick oilskin and wearing a primitive life belt, shading his eyes whilst looking out to sea, was erected on the sea front at Margate, overlooking Nayland Rock, where the tragedy took place. The names of all the men who lost their lives are carved on the base of the statue. It was also paid for by the fund.

It was argued that 15 shillings per week could at least be offered to the widows and half a crown (2s 6d) to each of the children but the idea was rejected out of hand by the Margate Corporation. And so the grief stricken boatmen’s wives and their children received not a penny from the benefit fund and were, in effect, robbed a second time and left in want as a consequence.

Ill feelings at the council’s mistreatment of the boatmen’s fund soon made itself felt and the local press was outspoken in their criticism of the way in which the fund had been squandered but it seems to have had no effect on the whole sorry matter and the wanton misappropriation of the fund has never been satisfactorily justified.

Surfboats

The history of the surfboats is given on the website for The Mayor and Charter Trustees of Margate.

It was the shipwreck of the Dublin steamer Royal Adelaide off Margate with the loss of all 250 people on board in April 1850 that determined the Margate boatman to purchase a lifeboat for themselves.

Having raised the funds, the first surfboat, Friend of All Nations, was on station in 1857. In the great storm of 1877 she was wrecked after saving the lives of 38 men from 6 vessels.

She was replaced in 1878 by a new surfboat, with the slightly changed name of Friend to All Nations. The boat had been well built and survived the disaster of 1897, the damage being chiefly to the masts and rigging, which were repaired. She was last in use in November 1898 but she was damaged and, though repaired, never used as a surfboat again. A new surfboat was constructed, with the improvements suggested by the Board of Trade Report, and put on station in September 1899, with the same name.

In 1922 the boat was motorised following public donations, becoming the first motorised lifeboat in Margate. she was requisitioned for service in World War Two and eventually sank off Ostend in 1957 when she was a houseboat.

During their many years of service, the Margate Surfboats rescued countless vessels as well as saving over 500 lives.

Ed’s notes:

Some reports say six wives and fourteen children, others say five wives and seventeen children.

Though erected only two years after the loss of the crewmen, the statue of the the sailor wearing a lifebelt was clearly inaccurate but perhaps it was artistic licence, used to identify the sailor as a lifeboatman.

One hundred and twenty years after the Margate Lifeboat Disaster, I wonder how many holiday makers who stroll along the Parade glance up at the statue and wonder at its origins or even read the inscription.

We can only imagine the effect on the town of the tragic loss of nine men from the surfboat Friend of All Nations. No doubt for the older people, it brought back memories of the terrible day of 5 January 1857 when nine men, including William and John Emptage, had died when the lugger Victory was lost during the attempt to rescue the crew of the Northern Belle.

Susan Morris

Note:

John Benjamin Dike (1856-1897) was the grandson of Sarah Emptage (1789-1861) who married William Dike c1817. Sarah was the daughter of Henry Emptage and Ann Kemp and the granddaughter of Henry Emptage and Ann Peal.

Sources:

Inquest

Board of Trade Inquiry

The full report published by Plimsoll.org:

Manchester Evening News

Fund

Wikipedia: Friend to All Nations

Margate Surfboat Memorial (1)

Margate Surfboat Memorial (2)

Funeral

Thanet Advertiser 11 December 1897

Surfboats