Frank Sidney Smith was born in 1928, the son of Minnie Clara Smith, nee Emptage. At the time of Frank’s birth, Minnie Clara was living at Thanet Union Workhouse, Minster, Thanet. She continued to live there whilst he and his brothers were raised in a children’s home run by the workhouse.

Minnie Clara Emptage had married George J Smith in Apr-June 1919 just before she was twenty one. It is possible that Minnie was already pregnant as the birth of their son, Frederick J Smith, was registered in Jan-Mar 1920. He was just thirteen when he died in 1933.

Minnie had three more sons: Arthur R (known as Reg) was born in 1925, Frank in 1928 and Basil (known as Ray) in 1934. All three sons were given the surname of their mother’s husband but it seems highly likely that he was not their father.

Frank says of his mother, Minnie Clara, that she had a sad life and was secretive. And that, although she spoke of his father the detail was always different and so she kept the truth from him.

Minnie Clara had been born thirty years earlier, in July 1898, also in the Thanet Union Workhouse. She was the daughter of Rachel Frances Emptage, who was just 18 at the time and unmarried. No father’s name was given on Minnie’s birth certificate. Rachel was described as a domestic servant in Ramsgate.

Rachel’s parents were Albert John Emptage and his first wife, Annie Walker.

When Minnie was born, Albert was a well known boatman and as coxswain of the Margate lifeboat had taken part in a noted rescue of twenty-seven people from a passenger ship, ‘The Persian Empire’ the previous year.

In 1895 Albert’s wife Annie had petitioned for divorce and she had died in 1897. Following her death, Albert married Nellie Euden in 1898. So it is possible that circumstances at home meant that Rachel had to go to the workhouse to have her baby.

At the time of the 1901 census, when Minnie was two, she seems to have been living or staying with her g. aunt in Margate and her mother Rachel was a live-in servant at a hotel in Margate. However, Frank says that Minnie spent much of her life in the workhouse, so it seems she returned there before she was very old.

After Frank was born, Minnie continued to live at the workhouse, working long hard hours in the laundry but she also had various periods of work outside the workhouse and one of these was with a family in Ramsgate. The wife did not enjoy good health and the daughter was deaf and dumb but Minnie learnt sign language to communicate with her. When Frank was about four, Minnie went to Italy with the family for a year from 1933-34, as a servant.

Minnie gave birth to Basil in 1934, in Turin, Italy. Was the master of the house Basil’s father? Had he got Minnie pregnant for a second time? Was Basil a half brother to Frank or was he actually a full brother?

As an adult, Frank revisited Margate and went to see his mother’s friend Susan, who had also been a servant at the house in Ramsgate. Not only did Susan give him a book on figure drawing which had once belonged to her master but there was a bust of a woman who looked like his mother. Was the ‘master’ his father? Was it from him that Frank had inherited his artistic abilities?

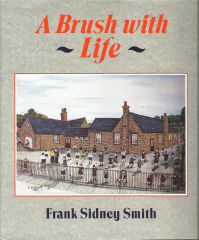

Thanet Union Workhouse

Not only did Frank not know who his father was, the workhouse system meant that he was largely separated from his mother during his childhood. The babies were kept in a separate area, looked after by nurses whilst the mothers worked. Although able to visit and to take the babies out, the mothers were given little opportunity to show love and were not allowed to breast feed them. The babies were christened in a chapel in the grounds of the workhouse.

At eight or nine months, the babies were removed to the Children’s Home at Manston, which was a couple of miles away and meant that visits from the parents became restricted to once every three or four weeks.

Manston Children’s Home

When Frank’s mother was working away from the workhouse, with little time off, her visits became even more infrequent and sometimes on visiting day, Frank would find himself waiting for her at the gates, crying because she didn’t arrive.

Although he had no family life, the Children’s Home was a well run and caring place with specially built houses and cottages, House Fathers and House Mothers. The younger children lived in a small house until they were old enough to go to school and moved up to the next house, with girls and boys in separate rooms. Later they moved to one of the cottages, each holding twelve boys or twelve girls. At age fourteen they went out into the world to work.

Up at 6.30, washed and dressed and beds made, the children were inspected before they left to walk the five minutes to school but though there were a lot of chores to keep the place clean, and regular darning to mend the holes in their socks, it wasn’t all strict discipline.

There was fun, toys, coach trips to the seaside and the fairground at Margate, and presents at Christmas. They were given a penny to spend at the village sweet shop on Saturdays.

And, if someone had been good, as a special treat, they could scrape the skin from the rice pudding dish. It was especially enjoyed by Frank though, as he frequently seemed to get into mischief or do something wrong, perhaps he didn’t get to scrape the dish very often.

The older boys went to Scouts and the younger boys to Cubs. There were prayers to be said at bedtime and church on Sundays. On Fridays they had to force down a spoonful of hated castor oil. And Friday night was bath night.

As they got older, the chores became harder. On Saturdays everything had to be scrubbed, and polished, furniture and windowsills dusted, the grates black leaded, the toilets cleaned and disinfected, the kitchen left spotless. But Frank remembers that the work didn’t bother them, that there were plenty of laughs and that they were proud of themselves afterwards.

He also remembers the fun of building snowmen but that the fun didn’t last long because he got chilblains. There was no heat in the cottages except a fire downstairs. His woollen gloves got soaked and his chilblains hurt so much that they made him cry.

Frank didn’t do very well at school, at reading and writing, partly because he was pining for his mother, presumably even more so when she was away in Italy for nearly a year, and partly because he shared a desk with one of the boys from the village. The boy was nicknamed Stinker and he smelled so horrible that Frank couldn’t concentrate. And so Frank often found himself in the corner wearing the dunce‘s cap.

When he was five or six, Frank nearly died from pneumonia. He was rushed to the children’s ward at the workhouse infirmary where his mother was allowed to visit often. As he recovered, Minnie took him out into the grounds, in a push chair. He saw other people who lived at the workhouse, including First World War veterans with an arm or leg missing.

Frank remembers that some outsiders, children who had unexpectedly found themselves in the children’s home, tried to run away. But those who, like him, had been born in the workhouse were so used to it that they never thought of running away. The Children’s Home was their home.

On 1st August 1939 Frank’s childhood abruptly ended. War was approaching and the children’s home was next to Manston airbase. There were fears that the airbase would be bombed.

With no chance to say goodbye to their friends, he and his brothers, together with their mother, were evacuated to Birmingham and the start of a new life.

Initially together in Birmingham, as war became closer, the children were evacuated into the countryside. Frank’s older brother remained in Birmingham as he was now fourteen, old enough to work. His mother was in service once more.

Years later, in 1960, the Birmingham newspaper printed a photograph taken on the day that the children were evacuated from the city to the country and Frank was astonished to find himself in the forefront. He was wearing his workhouse overcoat and, as he said, his hair parted on the girl’s side, not knowing anybody, not knowing where he was going or what was to happen.

But he found himself in the countryside living with a nice elderly couple. Even though there was the blackout to contend with, there were new experiences including close contact with hens, pigs, cows, bullocks and geese and farmers to help. The children made a pool in a stream and learnt to swim. But they still weren’t far from Birmingham and Coventry and some of the bombs fell very close. Even so, it was one of the happiest times of his life.

When he was old enough to leave school, Frank went to live with another couple and to work full time for a farmer, earning thirty shillings a week and paying his way for his lodgings. He stayed there for a year and enjoyed a very happy time.

In 1943, his mother remarried and Frank went to live with her and her new husband in Birmingham. He was excited and happy and thought it would be lovely.

But Henry Fessey was a tall strong man, “a horrible man, bed-tempered, bad mannered and violent” and Minnie was not capable of standing up to her husband nor stopping Frank being hit by him. They kept most of his wages when he started work, giving him just a shilling pocket money.

The home which Frank had always wanted was not a home at all. There was no love there. After a year, Frank left. He found digs with an Irish lady with a kind heart and found a lot of happiness.

When called up for National Service in 1946, Frank signed on as a regular soldier and was in the army for eight years, serving in Palestine and Greece before transferring to the Royal Marines and volunteering for Korea, sailing in 1952.

[Frank was badly injured in Palestine, with the bullet remaining inside him for several years and not discovered until thirty eight years later by an x-ray following severe stomach pains.]

Whilst on active service, Frank saw an advert in a magazine from a girl named Doris Palmer who wanted a pen friend. They began exchanging letters and got engaged.

But unknown to him, both Doris and her parents were unstable mentally. Doris suffered a nervous breakdown on the day they’d planned to marry and was hospitalised. She seemed to recover and they married in 1954, set up home and had two sons, Roger and Gregory. Frank‘s two brothers lived nearby.

Doris suffered severe depression after the birth of both sons and was unable to take care of them properly when they were babies. Frank says that “when she was well, she was a marvellous mother, and I loved her deeply”.

Doris had become schizophrenic and was treated with lithium. The hospital prescribed far too high a dosage over two years and, unknown to Frank, her increasing problems and physical illness were actually caused by the medication which was meant to help her. Finally she was in intensive care and in a coma but the hospital gave Frank no explanations for her condition. Nor did they tell him when she was near to death, and so, although the family had been visiting earlier in the day, there was no family with her when she died in 1979.

The first Frank knew of the reason for his wife’s death was at the Registrar’s office, when he went to register her death. The letter from the hospital said that the cause of death was lithium poisoning. Subsequently, the coroner stated that it was death by misadventure. The shock almost destroyed Frank. It took nearly ten years and the help of a solicitor for the hospital to admit responsibility.

Roger never got over his mother’s death. He developed depression, began drinking and taking street drugs and became schizophrenic. He was often violent. Though taking some prescribed medicines, understandably he refused to take the lithium which had killed his mother. He was often hospitalised and finally, in 1988, he threw himself from the balcony of his flat and died.

A Brush with Life

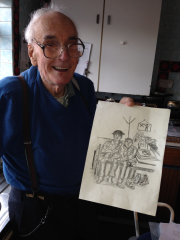

Frank had a difficult start in life and important parts of his adult life were quite traumatic. His life was emotionally gruelling and would have finished many people. And indeed, there have been several times when Frank has wondered how he has kept going. He feels that it was his painting which helped him the most, which kept him sane during the strain of what happened to his wife and son. His art became his therapy, a way of processing his life and understanding himself.

Frank says “Even in the middle of a time of sorrow you have to find some way of putting the sorrow to one side, and find a place where you can be yourself. For me, that place is a room with a canvas”.

He’d been dabbling for some years but in 1976 Frank started going to night school and in 1981 aged fifty three, Frank proudly passed his first ever public exam, getting Grade A in O-Level Art.

Frank decided to paint his autobiography and began the series of paintings which depict his life in such detail. In 1976 he went back to the workhouse, which was then Minster Hospital, so that he could make sure he got the details right. He stood crying and speechless as he saw the buildings and remembered his childhood of over forty years before.

And then Frank was shown the register with the entry of his christening. “Suddenly I knew there was no need to feel embarrassed. Instead I felt proud, and knew there was work to be done, recording all those buildings which had sheltered so many destitute mothers and unemployed men and poor children without proper families.”

Frank’s paintings are not fantasy but depict, in careful detail, the places and the people Frank encountered through his life. He gives great attention to the surroundings and has often returned to places to ensure that the detail was correct.

He has painted over 500 scenes from his life. They show a life begun in the workhouse, his time in the children’s home, war time evacuation, farm labouring, eight years army service, his work on the assembly lines at Austin Cars and Land Rover and the area of Birmingham in which he lives. Frank’s humour comes across in his work, plus his ability to remember the good times as well as the bad ones.

Frank’s biography ‘A Brush with Life’ was written when he was sixty five, in conjunction with John Man, and was published in 1993 by Weidenfeld and Nicholson. There are 130 colour illustrations depicting Frank’s life, the characters he met, the experiences he had. The paintings and the accompanying explanations have provided much of the information about his life detailed in this article.

“An Extraordinary Work of Social History”

When Frank was interviewed on BBC television, there was an overwhelming response from the art world to see his work. Number Nine the Gallery staged an exhibition which was previewed on BBC news and the following day there were queues outside the venue in the centre of Birmingham. Within ten minutes of the exhibition opening, all the paintings had been sold.

Anthony Daniels, writing for The Telegraph after interviewing Frank in 2001, described painting as Frank’s raison d’etre.

He wrote: “Frank Sidney Smith is both an ordinary man and an extraordinary one. He is voluble and more than delighted to tell his life history, his words tumbling out as if his thoughts outrun the ability of his speech organs to articulate them. His opinions are irrepressible.”

“His pictures cannot be judged in isolation from one another. Because they are narrative, they each benefit from a few lines of explanation. Their effect is strongly cumulative, and they have a quality of absolute and uncompromising truthfulness. Mr Smith cannot paint a lie. I know of no paintings that allow the viewer to enter so immediately and so intimately into the life of a child in an institution: the brown-and-cream walls, the bareness of the dormitories, the rituals such as the weekly dosing with castor oil and the insistence on eating the last mouthful of mutton fat.

“But the pleasures are caught as well as the pains: the Christmas treat, the coach outing, the pillow fights. Mr Smith loves his paintings, as if they were his friends. “Look at this one,” he says, “it’s one of my favourites. It’s a lovely painting.” His affection for his work is so genuine and touching that it doesn’t seem remotely egotistical.

“The paintings have the power to move deeply, despite their technical limitations. We see visiting day at the children’s home, for example, when parents could see their illegitimate offspring for a short time once every three or four weeks. It takes place in a large hall with bare brick walls, on eight bare wooden benches. The picture is at once intensely emotional and studiously objective, avoiding all trace of self-indulgent sentimentality.”

Anthony Daniels described Frank’s range: “both of emotion and of subject matter, is far wider than that of the vastly more celebrated L.S. Lowry. One feels that, if not quite all, then at least much of human life is there. His autobiography in paintings is a most remarkable human document, of considerable aesthetic value; but it is also an extraordinary work of social history.”

There is a brief video of Frank at the Library of Birmingham.

In 2008 he was featured by the Birmingham Mail, which wrote that he was “being hailed him as one of the art world’s most exciting newcomers at the age of 79“.

Turner Fine Arts of Birmingham has a page devoted to Frank’s work.

And The New Art Gallery, Walsall also features one of Frank’s paintings.

Susan Morris writes:

As I read Frank’s story, I couldn’t help thinking of my grandmother, Sophia, who was born in Thanet Union workhouse on 5th December 1897, the illegitimate daughter of Mary Palmer, a domestic servant in Ramsgate.

Frank’s mother, Minnie Clara was born in Thanet Union workhouse on 29th July 1898, the illegitimate daughter of Rachel Emptage, a domestic servant in Ramsgate.

Unlike Minnie, who was to spend most of her first thirty to forty years or so in the workhouse, three months after Sophia was born, she and her mother were living in Canterbury, where Sophia was adopted by James and Emma Wallis and became Emily Sophia Wallis. Although Emily went on to marry Walter Danzy Emptage and have twelve children, there were difficult times in her life too, with her husband.

Frank’s story of his time in the Children’s Home reminds me of the time that my brother and I spent in a children’s home.

We were more fortunate in that we spent just two months, December 1956 and January 1957, in a council run children’s home in Herne Bay, Kent, whilst our mother was in hospital.

Although this was sixteen years after Frank left the Children’s Home in Manston, I can imagine that it was run on similar lines. It was a smaller establishment, with just one house with girls and boys segregated in different rooms. I was eight and I remember putting up a fight, insisting that my very frightened younger brother be in the same room as me. Finally they capitulated but insisted that a screen be put around his bed so that he couldn’t see me or the other two young girls in the room. At least he knew I was near and we could talk to each other.

I knew what it was like to wait for a parent’s visit. I think our father tried to drive from Middlesex weekly but it was during the Suez Crisis and there was petrol rationing. After each visit I witnessed my brother’s terrible sobs after our father had left. I was old enough to know that we were only staying there whilst our mother was in hospital but he was three years younger, frightened and bewildered, too young to understand.

I can understand what Frank said about the outsiders, the children who arrived in the home unexpectedly and tried to run away. Thankfully I realised that we were different to most of the other children, who didn’t have visitors and who had no home to which they would return. I knew that John and I would be going home and we just had to stick it out.

And finally, I feel that I can understand Frank dreaming of a family life and being so happy when his mother remarried, leaving a job he loved and going off to live with her and her new husband, only to have his hopes and dreams dashed by ill treatment from that man.

I am so glad that Frank found the means of preserving his sanity as he dealt with what life threw at him and, in the process, that his art has given pleasure to so many people. And I am so pleased that I am fortunate to have a copy of his book.

Susan Morris

January 2015

Sources

‘A Brush with Life’, Frank Sidney Smith and John Man, published by Weidenfeld and Nicholson, London, 1993.

http://www.telegraph.co.uk/culture/4721908/A-life-lived-for-painting.html