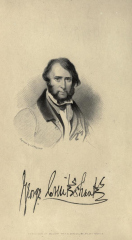

“A Short Cruise at Margate”, by George Cruickshank,

published in George Cruickshank’s Omnibus in 1842

Being at Margate the other day, we strolled in company with “The Old Sailor” down to the “Jetty,” where we were accosted by the veteran Hemptage, a boatman of the old school, who, with a salute, inquired “Will you take a trip this morning, Sir?”

“Not if it blows,” answered the Old Sailor, assuming as much as possible the looks and manners of a landsman, “I have made up my mind never to go sailing if there’s a breath of wind.”

The old man gave him a look, which spoke plainly as look could—”Here’s a precious lubber, to talk of sailing without wind.”

“It would be onpossible [sic] to move a-head and no breeze, Sir.”

“I don’t care for that,” rejoined the Old Sailor, “I am very timid on the water; but if you’re sure there’s no danger, and it will be quite calm (it was nearly so), I will venture to take a sail.”

“Danger!” repeated the veteran somewhat contemptuously, though there was an expression of doubt and suspicion on his countenance that seemed to say “I think you’re a gammoning me.”—”What danger can there be when there’s hardly wind enough to fill the canvas?”

After some further conversation relative to the perils of the ocean, which drew forth some scornful glances from the veteran, we embarked in a pretty green boat, with two masts or poles, one sticking up behind and the other near the middle, to which sails were fastened. Whilst Hemptage was loosing what we believe is named the main-sail, the Old Sailor jumped aft to set what he called the “lug mizen,” and he was shoving out a pole from the stern, right over the water. We immediately informed the boatman that our companion was “meddling with things at the other end,” and the veteran promptly turned round and exclaimed, “You’d better let that ere alone Sir. You’ll find somut as ‘ull puzzle you there.”

“Avast, old boy!” returned the Old Sailor, laughing; “I’ve rigged out as many bumkins1 as you have in my time.”

“Ay, ay,” drawled out the veteran—”hang me if I didn’t think so by the cut of your jib—I thought it was gammon, and you knowed better than to go sailing without wind.”

“You have belonged to a man-of-war,” said the Old Sailor, as we were standing of from the shore.

“Why, yes, I’ve had a spell at it,” returned Hemptage somewhat knowingly, “I was in the owld Hyacinth with Tommy Ussher, and a better Captain never walked a ship’s quarter-deck. I was with him too in the Ondaunted frigate up the Mediterranean—”

“What! were you in her, in Frejus Bay, when Buonaparte embarked for Elba,” enquired the Old Sailor.

“Why to be sure I was, and I remembers it well enough, ” returned he with animation. “And the first thing Boney did when he got aboard was to come up forud on to the foksle and have a yarn with the foksle men2.”

“What sort of a man was he?” we asked with quickness.

“What sort of a man,” reiterated the veteran, “why a stout good-looking chap enough, only very swarthy. Them images as the Italian boys brings about is very like, only I never seed him in that little cocked hat.”

“Why what did he wear then?” inquired we with some eagerness.

“Oh he wore a round hat3,” replied Hemptage, “and he used to lean against the breech of the foksle gun and spin yarns with us for the hour together.”

“Well!” we thought, “we never shall have done with Boney.” We had never drawn him in a round hat, and the temptation was too strong to be resisted—so we have accordingly placed him at the head of this article—and as of course he would have a fashionable beaver, we have given him one of the shape of that period, and placed him in contrast with himself.—Boney versus Boney—cock’d hat against round.

It may be said “What’s in a hat?” And when upon a head it becomes a rather important question. In many cases the answer would be “not much,” but with respect to Napoleon it certainly must be admitted that there was something in it.

“But (we asked in continuation of our conversation) how could you talk with Buonaparte—did he speak English?”

“O yes, pretty well, considering—very well for him, ” replied Hemptage, “he mixed a little of his own lingo up with it—but we made it out. During the passage he used very often to come forud, and he told us he liked English sailors, and the one had wounded him once at Toulon.”

Fully aware that the fact of Napoleon’s being wounded at Toulon had long been a disputed point, we questioned the man, and received the following statement:—

“Why,” said the veteran, “he told us how the English made a sortie, as they call it, and drove the French before them. Boney ran as well as the rest, and an English seaman chaced [sic] after him; but whether the man was tired, or thought he’d gone far enough, he didn’t know, but gave him a shove in the starn with his bagonet, [sic] and said, TAKE THAT, YOU FRENCH LUBBER.” The sailor might have killed him if he had been so disposed, but he acted generously and spared his life. ‘And,’ says Boney, ‘if ever I could have discovered the man who acted so nobly, I would have made him comfortable for life.’ The wound was in his thigh.”

Now had that Jack Tar taken one step further, or have made a deadly thrust, the fate of Major Bonaparte would have been sealed at Toulon, and the world would never have heard of the EMPEROR NAPOLEON. We fancy we hear some of our Hibernian friends exclaiming, “Faith, then, and it’s a pity the sailor didn’t know that Boney would be after doing so much mischief.”

Thus conversing and moralising, we finished our “Short cruise at Margate.” Hemptage is approaching his seventieth year, and his countenance displays the colours of a thorough seaman. He has been several times wounded, but looking hale and hearty. When paid off he was refused a pension—visitors will find him a pleasant shipmate in a trip—and the lovers of the marvellous may enjoy the satisfaction of conversing with a man who has seen and talked with “a live Bonyparty.”

______________________________________________________________________

1 The bumkin is the spar that projects out from the stern to haul the mizen-sheet home.—Naval dictionary. Here, however, it is probable that a double entendre was meant.

2 In No. CXLIII. of the United Service Journal, Sir Thomas Ussher has given an interesting account of the embarkation and conveyance of Napoleon from Frejus to Elba, in which we find the following passage:—”On arriving alongside, I immediately went up the side to receive the Emperor on the quarter-deck. He took his hat off, and bowed to the officers who were assembled on the deck. He then immediately went to forward to the forecastle amongst the people, and I found him there talking to some of the men, conversing with those among them who understood a little French.”

3 In another part of the same article, in the United Services Journal, Sir Thomas Ussher says—”this evening a small trading vessel passed near us, I ordered her to be examined; and as Napoleon was anxious to know the news, I desired the Captain to be sent on board. Napoleon was on the quarter-deck—he had a great coat and round hat on.” At another place, after their arrival at Elba—”At eight, the emperor asked me for a boat, as he intended taking a walk on the opposite side of the bay. He wore a great coat and a round hat.”

______________________________________________________________________

George Cruickshank was a British caricaturist and book illustrator whose illustrations included many for Charles Dickens and other authors.

An omnibus was not only a long motor vehicle for passengers (a bus) but was also a printed anthology of the works of one author.

So it seems that Cruickshank’s ‘Omnibus’ was not only a collection of his observations and writing but also of his own illustrations to the stories. And, being a collection of stories, each one could have been written several years before it was published in 1842.

His story of meeting the veteran seaman Hemptage at Margate Jetty has come to us by way of the Google project to make the world’s books discoverable on line. The inside of the front cover shows that George Cruickshank’s Omnibus, published in 1842, was on the shelves of the libraries at The University of Michigan before being digitised.

I have transcribed the story for easier reading but to view the original, go to:

https://archive.org/stream/georgecruikshan00blangoog#page/n166/mode/2up

Susan Morris