Eileen was born at home on 17th November 1921, at 10 Mill Lane, Canterbury.

Her parents were Walter Dansy Emptage and Emily Sophia Emptage, formerly Wallis.

Walter was a civilian clerk at the A.P.D, the Army Pay Department at Canterbury Barracks.

Eileen was my mother. This photograph from the family album shows her aged about 18. She was the second eldest of twelve children, including twins, born to Walter and Emily.

Twins clearly run in our branch of the Emptage family as Eileen’s father had twin brothers, Edward Lindsey and Charles Frederick (Charley) and twin half brothers who, sadly, died as babies. Edward Lindsey also had a set of twins, one of whom, David Lindsey, is co-editor of this website. And one of Eileen’s siblings also had twins.

Walter and Emily set up home with Emily’s mother, Emma Wallace at 10 Mill Lane. Conditions must have been rather cramped as, by the time Emma died in 1936, ten grandchildren had been born, one had lived just two years and another was on the way. The youngest child was born in 1939.

Both of Eileen’s grandfathers had died by the time she was born but, as the family lived with her maternal grandmother (Eileen was 15 when Emma died) and her paternal grandmother, Malbry Jane Deamer (formerly Emptage, born Wilson) also lived in Canterbury, presumably she must have known both her grandmothers quite well.

Eileen’s mother Emily was an adopted only child but her father, Walter, had a sister and a brother (having lost one brother in the first world war). So, Eileen had two living grandmothers, an uncle and an aunt, and yet I have no memory of her mentioning any of them.

Of course, when we’re young, we accept things as they are and don’t think to ask the questions which we’d all love to ask now, especially those of us who are family historians.

On one of our family trips to Canterbury to see Aunt Joan and her family (the only one of Mum’s siblings who still lived there) my mother directed us past the house in Mill Lane. The house opened straight onto the pavement and she told us of the time when her mother had kept a would-be boyfriend chatting at the front door whilst she had sneaked out of the back door to go and meet her actual boyfriend.

Eileen was an intelligent girl. She won a scholarship to the Simon Langton Girls’ Grammar School in Canterbury and went there a year early. Without the scholarship, it is highly unlikely that the family could have afforded for Eileen to attend to the school. I remember her saying that she got a bit complacent, a bit lazy at one time and found herself put down a year as a result. She found that very annoying and she quickly worked her way back up again.

There were two injustices at school which Mum never forgot. Instead of being congratulated on receiving 98% in one of her Latin exams, her end of year report for Latin said ‘could have done better’. She was extremely miffed by that. And then there was the time when she inadvertently stepped back on to a prefect’s toe. She immediately apologised but the prefect snapped back that “it’s too late to apologise now”. Mum’s retort “So you’re meant to apologise before doing something?” didn’t go down well with the prefect.

I don’t know if Eileen was particularly sporty at school though I know she played lacrosse. Even as a mum of several years she could do impressive high kicks and could bend over and touch her toes, which I could never do!

Eileen was definitely musical and had a good singing voice, too. However, when learning to play the violin she was banished to the attic to practise because of the terrible sound she was making so Eileen soon gave that up and learnt to play the piano instead. Some years later, she joined a church choir when we lived in Devon.

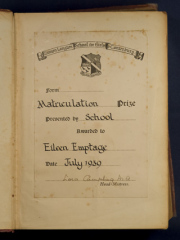

Eileen passed her matriculation examination in 1939. It was the requirement for taking university entrance exams or for taking commercial courses for entering business.

The Whitstable Times and Tankerton Press reported the school’s Seniors’ Prize Giving. It was held in the Chapter House of Canterbury Cathedral on 20 July 1939. Eileen was one of ten girls awarded their Matriculation certificates and prizes.

I don’t think I ever saw the certificate but I still have the prize which Eileen received.

It is an edition of The Works of Shakepeare, in a burgundy leather cover with gold coloured embossing on the spine and the name and crest of the school stamped in gold on the front cover. Admittedly, it doesn’t look quite so smart now but then it is very nearly seventy six years old and has been packed up and moved around the country many times.

Eileen may have wanted to go to university but the family would not have been able to afford for her to do so and she would have been expected to get a job and contribute to the family’s finances.

In 1939 there were three main opportunities for girls who were looking a for a good job: nursing, teaching or the civil service. Many schools actively encouraged their brightest pupils, girls and boys, to take the Civil Service entrance examinations.

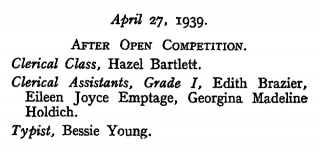

On 12 May 1939, pages 3210 and 3214 of The London Gazette (which reported on the appointment of civil servants as well as military personnel) listed the appointment of Clerical Assistants, Grade 1, whose Certificates of Qualification, obtained through open competition, had been issued in April.

Eileen Joyce Emptage received her certificate on 27th April and was assigned to the Post Office.

The British Postal Service Appointment Books show that Eileen, aged seventeen, joined the service on 1 May 1939 as a clerical assistant in the District Manager’s Office (Telecommunications) in Canterbury.

I remember my mother talking about her time as a telephonist, a member of a team operating a large manual telephone exchange before the days of automatic telephone exchanges. Although their title was telephonist, they referred to themselves as operators.

Telephonists were regarded as having good jobs. They had to have good speaking voices and be over a certain height to be able to reach the top sockets of the junction boxes.

The photograph, courtesy of Milton Keynes Telephone Museum, shows how the operators worked, with a supervisor to a group of operators and then an overall supervisor.

Having had elocution lessons at school, Eileen certainly had a good speaking voice, which remained with her all her life. I can still remember the voice and speech exercise which she used to recite. Eileen had enviable deportment which I fear I’ve never achieved though I’m not sure I’d have wanted to walk around with a pile of books on my head as her deportment training required. And she was taller than average, having to buy flat heeled shoes when she met her future husband.

War broke out two months before her eighteenth birthday and, as with so many young people, any plans Eileen had for her future were scuppered. Plus, the war had long term ramifications for her family life.

Canterbury and the surrounding villages were within easy reach of German planes and I remember my mother telling us that the road she had been walking along had been strafed and she’d taken cover in a doorway. It was not a safe place for a family and some of the children were evacuated but they were separated and sent to different places. To keep the family together, Emily took the children to Yorkshire (where, it is thought, her husband was stationed). As Eileen and her older sister Joan had left school and were already working, they stayed in Canterbury. After the war, Emily and the children remained in Yorkshire where the children were established at schools and where they had friends.

War Time Service

Being a telephonist in war time was a hazardous experience. The service had to be maintained 24 hours a day, 7 days a week no matter what was happening, even in the midst of the German bombing.

My mother said very little about her war time experiences and so I have extracted information from the lives of other war time telephonists, who contributed their experiences to a BBC history programme: WW2 People’s War: memories written by the public.

According to Harold Pollins, when the planes were getting near, his sister and the other operators at the Clerkenwell telephone exchange, in the City of London, would take their issued tin hats and “repair to the basement where there was an auxiliary exchange unit. There they continued their work, accompanied by cockroaches, other bugs, and rats, possibly disturbed by the bombing, or possibly because it was a very old building. The telephone operators slept there for the rest of the night and in the morning would start the day shift.

Pam Cuthbert recalled that “At sixteen [1940], I wrote to the GPO to apply for a job as telephonist, and was accepted. The first day I had to go to Old Street for training. At the weekend there had been bad air raids, especially the east end of London. I was climbing over the firemen’s hoses etc. All the time I was there, the bombs were falling. It was very noisy. After a week I was sent to Faraday House, a few yards from St. Paul’s cathedral. A much bombed area.

“In those days it was the Trunk exchange. Callers had to dial trunks for calls outside London. It was very busy. When the training was finished I was put on the duty rota. The shifts were very funny times. One lasting for two weeks, we called up and down duty. From seven am to twelve noon, one day, the next day, twelve noon until seven pm. which meant in the winter I was going home in the dark and every other day, arrived in the dark. Eventually they built bedrooms with bunk beds in the basement. When we came off duty at seven pm we stayed there. There was also a common room and a canteen. The latter was on the seventh floor – the top floor of the building. The exchange was built on six floors, two switch-rooms to a floor. I worked on the third floor. One day, a buzz bomb cut its engines, we all stopped speaking, you could have heard a pin drop in the silence. A supervisor called out, “Get on with your work!” So, we did. Hard times!

“One night when we were sleeping in the bunks, we were woken and told to dress and go to the common room. There was unexploded bomb in the courtyard between the four walls of the building. A friend and I decided to go back to sleep, fully dressed.

“In the canteen there was no water, electricity or gas. For breakfast, we had a glass of milk, and bread and margarine, also marmalade. When we got to the switch-rooms, there were candles on the top of the seven-foot high boards! It was chaos, people had difficulty to get through to us, and we couldn’t get through to them without difficulty. The bomb had severed the water, gas and electricity mains. I was very glad to get off duty, out of the mad house. In the night, buildings opposite us and all along the road were afire. I think it was 10th May 1940. It was a very dreadful night of air raids on London. Communications was considered an essential service, and we were not allowed to leave. Really, I would have liked to join the WRNS, but I wasn’t able to because of working at the exchange.

“I thought it was rather unfair, working during the air raids and not having any pleasure time, so I went to the cinema and to dances, causing my parents a lot of worry. When you are young, you don’t think of that!”

Pam Cuthbert wasn’t the only person who liked going to dances for some fun after work. My mother loved dancing and I remember her telling of one occasion when she was dancing with a Polish officer. When the music ended they found that the buckle on his Sam Browne belt (which passes diagonally over the chest and shoulder) had caught in the ruched bodice of her dress. The officer behaved impeccably, standing to attention and not looking down, as she struggled to free herself.

Hazel Stamp recounted her and her father’s experiences at Southampton Central Exchange. “We were on duty at all times, often having to evacuate our switchboard, on the top floor of the building in the centre of the town to an overground shelter close by.

“Then came our big blitz on 30 November 1940. I was on overtime on late duty, my father, a night operator was also on duty that night. We received Air Raid warning Red, then a double Red and we were evacuated to the shelter. An incendiary bomb fell at the entrance to the shelter and another set fire to the roof of the exchange building. The top floors of the building were burnt out and the remaining floors and equipment severely damaged by sea water from the fire hoses resulting in a total loss of telecommunications in and out of the town.”

“The PO Engineers erected a small hut in Southampton Parks near a main cable route to start a contact with the national telephone network. My Father had to leave home on the last bus at 6 pm to be on duty at 10pm to sit in the Parks overnight in winter to maintain the minimum of essential communication.

Hazel Stamp concluded her reminiscences by saying “I wonder why my colleagues and I and telephonists throughout the country were given very little recognition for the essential work that they performed during World War 2.”

With all that I have read whilst researching the role of telephone operators in the war, I find myself posing the same question. I believe the telephonists and many others whose role in the war has been unrecognised for so long to be unsung heroes and heroines of the war.

When I started writing this article about my mother, all I knew of her war time experience was that she had worked in Worcester with an evacuated government ministry before moving to London. And that she had fond memories of Worcester.

The rest of this section is based on circumstantial evidence pieced together to form what I think is a credible and reasonable hypothesis.

My mother didn’t like being photographed and so, regretfully, there are very few photographs of her but there are two which I now find intriguing, especially since the date written in the album is 1941.

Of course, as children we simply accept things as they are, without asking questions and, to me, these were just two photos of Mum taken seven years before I was born, just as there were photos of my father about the same time, though he was wearing RAF uniform.

The first photograph shows Eileen walking along what looks like a wide seaside promenade, with typical Victorian or Edwardian bay window buildings in the background. As such, it is a scene typical of many seaside resorts around England and is without any clue as to where the photograph was taken.

The second photograph shows Eileen sitting in a deck chair on the beach with a building in the background. It is just a small portion of the building and almost looks like a multi storey car park, which puzzled me because I’m sure they weren’t around in 1941.

Initially I thought there was no possible way of identifying it but recently it occurred to me to remove the photos from the album and turn them over.

Bless my mother! The one of Mum walking along the prom is blank but, on the other one, written in pencil in my Mum’s writing it says “Me on the beach at St Leonards in front of Marine Court.”

Marine Court is an Art Deco apartment building, built in the late 1930s. With thirteen storeys, it was the tallest apartment building in the country and was designed to look like the cruise liner, Queen Mary.

Examining the various images of Marine Court available on the Internet it is possible to see the part which shows in the background of the photograph. The early images of the time it was built show the same type of street light which is in the photograph of Mum walking along the promenade and confirm that it was, indeed, a wide promenade. With the aid of Google Maps and Street View, I have identified the building past which Mum was walking, less than a quarter of a mile away from Marine Court, along Marine Parade.

You may be asking ‘What, apart from the date, has all of this to do with Eileen’s service in the war and what’s so exciting about St Leonards?”

St Leonards on Sea is next to Hastings, on the Sussex coast. As Eileen lived in Canterbury, it is quite feasible that she could have been there with a friend for a weekend. However, the two photos are taken at different seasons.

Walking along the prom Mum is wearing a winter coat. It was evidently cold because she has one hand tucked behind the other arm and the other hand tucked inside the opposite sleeve.

Sitting in the deck chair she is wearing a short sleeved blouse and a light weight summer skirt with a floral design and the sun is shining. It is a fairly smart outfit, not a casual holiday or beach outfit.

So, either she was there more than once in 1941 or….. she was there for an extended period.

In 2005, Mike Rose contributed to the BBC’s WW2 People’s War archive of memories. He was a boy living in the area during the war.

“Hastings and St. Leonards did not in the second world war suffer from heavy concentrated bombing as that of the larger towns and cities as the likes of London, Coventry, and Bristol etc. but was subject to frequent raids by lone or small groups of fighter bombers, raids known as Tip and Run. Just over thirty miles from occupied France, enemy fighter bombers came across at wave top height, turned over the town dropping their bombs and were gone in a matter of minutes. Often the first you knew of a raid was the sound of bombs exploding.”

A lot of the town was bombed and two thirds of the population was evacuated. It was evidently not a place to go for a relaxing summer holiday or long weekend in 1941 and I think that Eileen must have been there for an extended period. But why?

When war first broke out, even though it was the biggest employer in the country, the GPO wasn’t recognised as a reserved or essential occupation and of course many men enlisted, so women, already a high proportion of the work force, became even more important, many taking over the night shift which had previously been worked by the male telephone operators.

It took some time for the government to realise the importance of telecommunications and to belatedly declare it a reserve occupation.

Single women aged 20 – 30 received their call up papers in 1941 and were required to join the women’s military services or sign up for factory work (such as munitions) or farming (the Land Army girls).

However, by then, Eileen was already in a reserved occupation. Whilst she couldn’t have joined the WAAF (Women’s Auxiliary Air Force) WRNS (Women’s Royal Navy Service) or ATS (Auxilliary Territorial Service – women’s branch of the British Army) even if she’d wanted to, she could have carried out other duties within telecommunications or even have been transferred to another branch of the Civil Service.

For some time, my brother and I have wondered if she went to Bletchley Park where they had both service and civilian women engaged in the code breaking work. She certainly had the intelligence to do that type of work.

But, whilst it was the place for the Enigma code breaking work, Bletchley Park wasn’t the only place in England which dealt with coding and ciphers.

Cue Marine Court, St Leonards on Sea.

The National Archives has records relating to the Compensation (Defence) Act 1939 which show that the government requisitioned the building, from the owners Swales Estates Limited, for use by the Air Force which used it as an Initial Training Wing for new airmen, for the classroom learning.

However, according to an article published in The Guardian newspaper, it was also occupied by cypher clerks. The article was written by somebody who has lived at Marine Court for many years and knows its history. But, at the moment, I can’t find any other reference anywhere to cypher or cipher clerks in Marine Court.

The East Sussex archives appear to know nothing of activities at Marine Court during the war and the National Archives only has the reference to the Compensation (Defence) Act 1939. I have yet to check with local history societies or local reference libraries.

In the early 60s, we had a holiday on the Sussex coast. We stayed about 18 miles from St Leonards, which was where an uncle and aunt of my father lived. Of course, we went to see them, driving through Hastings and then St Leonards.

I remember stopping in Hastings to see the fishing boats drawn up on the beach. I remember the embarrassment of spilling my cup of tea in the lap of my best summer dress (grey shirtwaister with yellow roses) whilst trying to behave as a well mannered young lady on my first visit to see Pa’s seemingly ancient aunt and uncle.

However, I am certain that we didn’t drive past the Art Deco building, which my father most certainly would have taken a detour to show us had he known that Mum had any connection with the building.

And I am pretty certain that Mum gave no indication of having worked in Hastings or St Leonards.

Of course, being in the Civil Service, Eileen would have signed the Offical Secrets Act but that would surely not have stopped her saying that she worked in the building as a telephone operator. But would she have admitted to being anything else, either there or elsewhere? Would she have felt able to announce that she was a cipher clerk?

It is only just recently that some of the women who were at Bletchley Park are now telling their stories, in their 90s. Many women went to their graves without their husbands or their families knowing that they were at Bletchley Park.

So, what makes me think that Eileen was not just visiting St Leonards but worked at Marine Court?

On the photograph, Mum made particular reference to the building. She didn’t say ‘on the beach at St Leonards’ but made particular reference to being in front of that building. Of course, it could have been because it’s a unique building. But… it could have been because that’s where she worked.

My mother loved sun bathing and would take every opportunity to do so. So, to see her in a deckchair on the beach is to be expected but to see her dressed fairly formally whilst doing so is a little unusual. I think that if she worked at Marine Court she would have headed out into the sun at lunchtimes if she could.

Plus…..

Eileen became engaged to a Canadian during the war but, sadly, he went missing in action, believed killed.

I have the ‘sweetheart’ brooch which he gave to her. It has the Royal Artillery insignia of a mounted gun and the motto which was used by all the Royal Artillery from all the Commonwealth countries. It reads ‘Ubique’ which is ‘Everywhere’ in Latin and ‘Quo Fas Et Gloria Ducunt” which means ‘Where Right and Glory Lead’.

He also gave her a Canada maple leaf brooch.

Mike Rose, who contributed his story to the BBC Southern Counties Radio, remembered “the Canadians that were stationed all around” and in particular, the Bren gun carriers which the Canadians used to allow the small boys to hose down after they’d been out on exercise, rewarding the boys with a ride and small payment. Bren gun carriers would have been used by the artillery. He referred to a Canadian sergeant who lost his life on D Day.

Sadly, one of the German bombs fell on a hotel in the area which was occupied by Canadian soldiers and killed many of them.

Mike Rose also recalled “Other memories of the Canadians was when they used to carry out mock attacks on a building called Marine Court, a large 13 story apartment building that during the war was occupied by the RAF. The building was defended by the RAF and the Canadians used to get us boys to wander around the streets leading to the building and report back the positions of the defending RAF, with our reports and ably assisted by the women who used to let them through their houses to detour the defensive positions those defending were never in with a chance.”

Of course, Mum could have met her fiancé any where but, if she were working at Marine Court and St Leonards and Hastings were full of Canadian airmen and soldiers, it is highly likely that she met him there, quite possibly at a dance.

Perhaps my mother didn’t mention Marine Court and St Leonards because it was a place where she thought she’d found happiness only to have it taken away from her. Perhaps because she had witnessed horror and sadness. Perhaps because of the Official Secrets Act.

It doesn’t matter what her role at Marine Court was (though I’m inquisitive and would like to know). With the building having been taken over by the Air Ministry, she could have been there as a switchboard operator, a cipher clerk or even in another capacity. What matters is that she survived her time there, though at cost to herself.

It was probably after that time that Eileen transferred to the evacuated government ministry at Worcester. Unfortunately, the Worcestershire Archives are unable to supply a list of such ministry evacuations though they have documents which may contain information and would need checking.

There were just two bombing raids in Worcester, both in 1940, each by a single plane aiming at specific targets, with seven people were killed in one raid and none in the other. So it seems that by the time Mum would have arrived there, it was a more peaceful and relaxing place than Canterbury and St Leonards. As she said, she had fond memories of Worcester.

After the war Eileen moved to London but I don’t know if she went with the ministry when it returned to London or whether she transferred to a GPO telephone exchange in London.

The National Archives website states that it is difficult to discover any records about those who were in the Civil Service, unless they were famous or infamous, partly because there were so many employed all over the country.

How I wish I’d asked questions when I was young and my mother was still alive.

Family Life

The Electoral Roll for 1947 shows that Eileen lived not far from Hammersmith Palais and it was there, in 1947, that she met John Jefferys.

Hammersmith Palais was a mecca for dancers before and after the war, with people travelling quite some distance to dance there but fortunately for them, John was living in Kensington, not far from Eileen. She wasn’t that keen on him at first but they were both very good dancers and that was important to them. A few years later they found themselves wondering how they came to have a daughter who, despite their best efforts, simply had no sense of rhythm and couldn’t dance.

The photo was taken by my father in 1947, when Eileen was 25. I think she is sitting on the balustrade of the Serpentine Bridge which marks the boundary between Kensington Gardens and Hyde Park, London.

I was born on 29 April 1948 and John and Eileen were married three weeks later, on 22 May. John had been married previously and had been separated for some time. It took a long time to track his wife down and obtain a divorce. By the time he was free to marry Eileen, I was already showing as a large bump and my mother refused to get married in that condition. So my birth was registered immediately after they married. Later, my mother was concerned as to my reaction to my ‘illegitimate’ birth but both my parents names are on my birth certificate, including my mother’s married name, and it doesn’t bother me at all.

I was still a baby or toddler when we moved to Devon, where my brother John was born on 22 May 1951, on their wedding anniversary and not, as he used to say as a child, on their wedding day.

So, by the early 1950s, my mother was in Devon, her sister Joan in Canterbury and the rest of the family in Yorkshire.

Although my father had both a car and a telephone because of his work, I’m not sure whether the rest of Mum’s family had either. And, of course, cars were not fast and there was no network of motorways so there was little opportunity for Eileen to meet up with the rest of her family. Such a trip was a major expedition though we did travel from Devon to Yorkshire in 1950. Perhaps that trip was timed to take advantage of the end of petrol rationing in May 1950.

When we moved to Middlesex and London, we were able to visit Joan and her family in Canterbury. Allan and his wife Ilse, who had visited us in Devon, also visited us in London.

The photograph shows Allan and Eileen, with my brother, John, and me posing on Allan’s big red shiny Triumph motorbike in 1960.

Either John or Tony, if not both, brought their new wives to London on honeymoon and we met up with them. So there was a little more contact between Eileen and her family.

We went to Baildon, near Shipley, to stay with Emily in 1959 and also visited Hazel and her family in Lancashire at the same time.

Eileen and Joan went to see Emily not long before she died in 1961 and Mum inherited Emily’s wedding ring, which subsequently came to me. Joan inherited a ruby pendant which I wore on my wedding day as my ‘borrowed’ item.

One of Eileen’s favourite pastimes was to complete the Sunday Times ‘Mephisto’ crossword which is still considered to be an advanced cryptic crossword. And, as well as answering academic questions on television quiz programme, such as those relating to English, French, Latin, maths and music, she was also able to answer questions of a more cryptic nature. It was a small way for her to keep exercising her brain.

Eileen suffered for many years with ill health. She had a hysterectomy not long after John was born and also had to have her thyroid gland removed. These days a person who has the thyroid removed has to take thyroid hormone pills for the rest of their life but I wonder what happened in 1961 when Mum had her operation. Was she given thyroid hormone replacement therapy or was she left to fend for herself? It would have had a bearing on her subsequent physical and mental state.

Mum had many years of what used to be called ‘nervous breakdowns’ and also suffered from agoraphobia. Mental health problems are rarely caused by one event and I have long believed that the loss of her fiance, her war time experiences in Canterbury and elsewhere and especially actions by her father contributed greatly to the state of her mental health. However, since undertaking this research, I have a better idea of just what effect her war time experiences may have had on Eileen.

Eileen was an intelligent woman who had exercised her brain during the war years, whether as a telephone operator, a cipher clerk or any other capacity. Whilst she could have continued working after the war ended, she met my father in 1947, married him in 1948 and produced me. In those days, even if she wanted to continue working, there was still a bar on married women working in the Civil Service.

In a recent article about the female codebreakers at Bletchley Park, Marigold Philips spoke about her experiences, saying that, after the war, all she craved was ‘normality’.

“She summed this up as wanting to have: ‘In this order, a husband, a baby, a house and a car. I had no ambitions and I think that was very common. It had seemed so unnatural, the life we had led, that we swung too far the other way and of course a great many people bitterly regretted it.’

Marigold married an army officer with whom she had two sons and a daughter and was happy and content. However, she knew of other women who struggled to fulfill a role as a humdrum housewife following the important work they had carried out during the war.

She said: ‘We all heard stories of the young mothers with good brains who suddenly found they had a husband at work all day and two small children at home and went nearly batty with frustration. It was a quite severe social problem after the war.’

I can understand how a woman accustomed to exercising her intelligence would feel if she was suddenly cast into nothing but a world of domesticity.

Whether Eileen became a cipher clerk at Marine Court, St Leonards, or was there as a telephone operator, there is no doubt that she played her part in war-time England, maintaining communications, working through air raids, not being able to head for the bomb shelters. We can only imagine the effect that living such a life had on people, no matter how many dances they went to or how many times they went to the cinema in an effort to have some normality and distraction.

The photograph shows Mum and Hazel in November 1968, just three months before Mum died.

Eileen took her own life on 7th February 1969. She was just 47.

Since researching the family history, I never cease to marvel at the fact that my mother would go green if she so much as saw a television programme or a film with a boat going up and down on the sea and yet her great grandfather, and her 2 and 3 times great grandfathers were all mariners from Margate.

It was only when I started researching the Emptage family history and plotted their birth dates that I realised the age differences between my mother and her siblings and what it meant.

| 1920 | Joan, | 1927 | Allan, | 1933 | Brenda, | 1936 | John |

| 1921 | Eileen, | 1929 | Hazel, | 1933 | Stella, | 1938 | Jill |

| 1923–24 | James, | 1931 | Ena, | 1934 | Anthony, | 1939 | Colin |

My mother was nearly eighteen when Colin was born, war broke out within weeks and the family were evacuated to Yorkshire where they remained after the war.

It is clear that, whilst Joan Allan and Hazel probably had good memories of Eileen and knew her as an adult, some of her siblings would have only vague memories and the youngest wouldn’t have any memories of her at all. And, therefore, with the help of a few photographs, I have tried to give an impression of my mother, Eileen Joyce Emptage.

Susan Morris

24 May 2015