Today, there are many concerns about the influence of powerful global companies but the largest and most powerful company that the world has ever seen was The East India Company. It was the first major shareholder-owned business enterprise.

In the late 1500s, European explorers from the maritime nations of Portugal, Spain, England and Holland started sailing east in search of trading opportunities. The Dutch were mainly engaged in the lucrative trade of spices, which were essential to the preservation of food.

The English didn’t want to fall behind the Dutch and an association of some 200 merchants was formed in 1600, with the intent of obtaining silks, porcelain and tea from China, and nutmeg, mace and cloves from the ‘Spice Islands’, the Moluccas (now part of Indonesia), all luxury items.

A Royal Charter was granted by Queen Elizabeth I on 31 December 1600. Some of the merchants formed a group calling themselves the Governor and company of Merchants of London Trading into the East Indies. It was to become The East India Company.

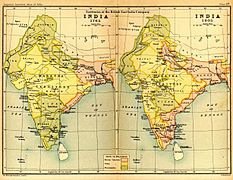

The first trading post in India was Surat, granted in 1615. Portugal ceded Bombay to the British in 1661 and it became the main trading post on the west coast of India. The British established a trading posts on the east coast, in Calcutta in 1686 and Madras in 1693. The maps show the East India Company Territories (in pink) in 1765 and 1805.

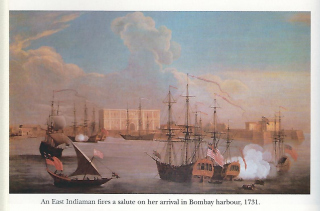

The Honourable Company (as The East India Company became known) came to control over half the world’s trade and a quarter of its population. It was a commercial enterprise but raised its own army and navy, minted its own currency and traded with every corner of the globe, establishing communication and navigation routes. The East India Company ships were known as East Indiamen. They were the largest ships of the time, built to the Company’s specifications and were known as ‘the aristocrats of the navy’.

The merchants may have received exclusive rights for a British company to trade in India and the Far East but they were in competition with the Dutch (who established their East India Company in 1602 to protect their trade in the Indian Ocean) and the French (whose East India Company was set up in 1664). Although it had some success with obtaining spices, the British Company decided that it really couldn’t compete with the Dutch in that respect and turned its attention to cotton products (calico, chintz and muslin) plus silk from India, employing skilled weavers to produce the materials which were popular amongst the British upper classes. By the 1700s the Company was dominating the global textile trade.

Between 1709 and 1748 lucrative trade with the three presidencies of Bombay, Calcutta and Madras grew steadily. Madras sent Indian fabrics to Indonesia and received spices in return and began to act as a staging post for trade in tea and porcelain from China.

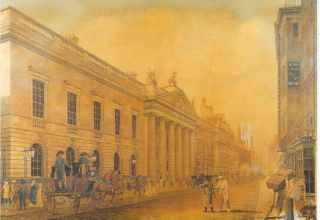

As with modern large companies, the East India Company had a prestigious headquarters, in Leadenhall Street, in the heart of the City of London which was and still is the financial and commercial centre of England. In the 1720s the building was given a new facade in the very best of classical taste.

But by the mid 18th century the industrial revolution in Britain had led to the mass production of textiles and thus lowered the prices. At the same time, there was a growing desire in Europe for tea from China and the Company switched its attention to that trade, making a fortune in the process, though by questionable means which led to the Chinese Opium Wars.

In order to protect its interests, the Company established private armies which grew in size to become larger than that of any European state and by the end of the eighteenth century the company controlled the whole of India, taking full administrative powers over its territories, including the imposition of taxes. Of course, this was not entirely welcomed and over time there was increasing insurgency and rebellion. In time, it would lead to the Indian Mutiny of 1857, which was not against the British army and rule, as I had always understood from school lessons, but was against the East India Company army and its rule.

The Bombay Marine

The company’s private navy was known as The Bombay Marine and is described by The British Library as “the fighting navy of the East India Company in Asian waters, as opposed to its mercantile marine.”

It was intended mainly for coastal protection, engaging with pirates and French privateers intent on taking the Company’s ships and goods. The Bombay Marine operated from the Persian Gulf to the Indian Ocean whilst also, from 1772, carrying out much survey work, not just off the coasts of India and its environs but also much further afield.

When a ship arrived in port, it would fire its guns in salute.

In war time, the Bombay Marine’s ships worked alongside the Royal Navy, primarily against France, both when Britain was at war with France and when France supported the Indians who wanted to reclaim their own territories.

The 1780s were a turbulent time in India, with fighting on land and at sea and the Bombay Marine took an active part in the Second Anglo-Mysore War (1780-84), a conflict between the Company and the kingdom of Mysore. France was a key French ally to the ruler of Mysore in India and the Franco-British war sparked Anglo-Mysorean hostilities in India. Both France and Britain sent troops and naval squadrons to assist their respective sides.

In 1782, in an effort to divert pressure away from the East India Company’s settlements and forces elsewhere, which were under sustained attack, it was decided to send a strong military and naval force from Bombay to take the hill fort at Rajamundroog, at the mouth of the river Merjee (or Merjan) under the command of General Mathews.

The force was conveyed south by the Bombay Marine ships, under the under the command of Commodore George Emptage, who flew his broad pennant on board the 28 gun ship Bombay.

Having taken Rajamundroog, the military and naval forces proceeded on to Onore. On 1st January 1783 the British batteries and the guns from the ships breached the fort at Onore and the fort was stormed. Further successes along the coast were achieved before General Mathews led his forces inland, encountering successes and reversals.

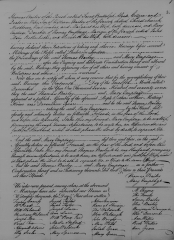

On 13 June 1783, George wrote a long report to the President and Governor and Members of the Select Committee on Bombay, concerning matters which had been raised by the President, about the sequence and circumstances of various events which took place from March 1783 onwards.

Honourable Sir and Sirs

Agreeable to the orders conveyed to me in a letter from your secretary of the 6th Instant I now beg leave to reply to the several matters therein contained ……”

It seems as though he was being called upon to justify his actions or the way in which events had worked out, even though in most cases these involved others, for whose actions he could not be responsible. Events were fast moving during the war and he was the person who had to make on the spot judgements, unlike those sat in headquarters in Bombay.

George concluded his report:

I have now honourable sir and sirs answered to all the matters you have been pleased to require of me in your order of the 6th instant. I hope fully and to your sirs satisfaction and having nothing further to add I shall beg leave to subscribe myself with the greatest respect.

Honourable Sir and Sirs

Your most obedient and

humble servantGeorge Emptage”

The war was to last several more months before a peace treaty was signed in March 1784 with neither side having gained anything.

To have risen to the rank of Commodore, the officer who commanded a flotilla or squadron of ships, indicates that George had knowledge, ability, skill and bravery.

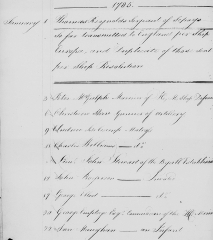

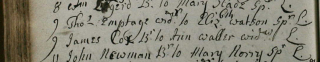

George’s record of service with the East India Company tells us that he joined as a midshipman in 1752. He would have been 19, which was actually a little old for a midshipman in those days, so I wonder whether he was sailing elsewhere beforehand. He was with the ship Protector until 1756 and then moved to the ketch Success as midshipman, third in command. He rose to second lieutenant and then first lieutenant and by 1764 he was third on the service’s list of 1st lieutenants. He was then on board the ship Revenge.

George became a captain in 1766 and from 1766/67 he was commanding the Cruizers at Surat. He returned to the ketch Success as captain in 1768 and spent time in the Drake and Bombay. From 1776/78 he is recorded as Provisional Superintendent.

On 18 April 1781 George became commodore, recorded as being on shore but we know that he was active at sea in 1783 at least. Sometime in 1784 he was admitted to ‘sick quarters’ but there is no indication if this was on board ship or whether he’d been brought ashore, whether he was suffering from injury sustained in the war or from illness.

George Emptage, Commodore of the Honourable Company (HC) died on the 20 January 1785 in Bombay, aged fifty two.

Whilst there are online references to the part that he played in the above action, so far it is the only action for which details are available even though, having risen through the ranks, he must have been engaged in several skirmishes, battles, minor and major actions.

The East India Company’s records are available at the British Library and it is possible that examination of these may elicit further information about George Emptage’s service with the Bombay Marine.

Who was Commodore George Emptage?

Thomas Emptage, widower and mariner, of Rotherhithe, married Elizabeth Watson, spinster, at the Collegiate Church of St Katherine by the Tower on 9 May 1732.

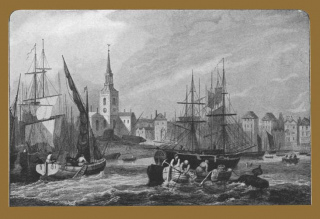

St Katherine’s, next to the Tower of London and down river of it, was on the north side of the river Thames (where St Katherine’s Dock is today). Rotherhithe was less than a mile down river from St Katherine’s on the southern shore.

In those days, the river Thames was a very busy London thoroughfare, with many small ferry boats conveying people between shore and ship, across the river from one shore to the other, and up or downstream as required. Travelling between the two parishes by ferry would have been second nature to those who lived by the river.

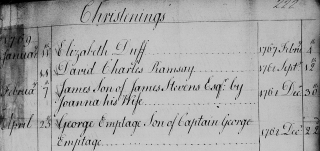

Their son George was baptised on 25 March in 1733, in St Mary’s, the parish church of Rotherhithe. A daughter, Mary, was born c1738.

The church of St Mary’s was at the heart of the village of Rotherhithe, standing not far from the riverside. When George was born, Rotherhithe was a thriving port on the south bank of the river Thames, with shipyards, working docks and warehouses. It was the first port to be built to benefit London and possibly derived its name from the Saxon redhra, a mariner and hyth, a haven or landing place. It was historically known as Redriffe.

Rotherhithe’s inhabitants were chiefly masters of ships and other seafaring people, or those associated with ship building, the docks and overseas trade and had been for many years. Indeed, Christopher Jones, who part owned the Mayflower lived in Rotherhithe, which was the ship’s home port. It was he who captained its 1620 voyage when it was chartered by a group of people who became known as the Pilgrim Fathers, to take them to New England, the New World of the Americas. Captain Jones would have had a crew of some 36 men and 14 officers on board.

So Rotherhithe had a fine tradition of seafaring and George would have grown up surrounded by all things nautical, listening to many tales of life at sea and of foreign places. It is little wonder that he chose such a life for himself. And, therefore, to follow in his father’s footsteps.

George’s sister Mary remained in Rotherhithe.

On 16 December 1777 she married Thomas Bailey, of Saint Buttolph, Algate. a dealer in wine. It was a Quaker marriage, at the meeting house near Devonshire Square, London. Mary’s parents were given as Thomas Emptage, mariner, of the parish of St Mary, Rotherhithe, and Elizabeth, his wife. Both were deceased.

Taking Mary’s hand, Thomas made his declaration to take Mary to be his wife. Then Mary took his hand and declared:

Friends, in the fear of the Lord and before this Assembly, I take this my Friend Thomas Bailey to be my husband, promising through divine assistance, to be unto him an affectionate and faithful wife, until it shall please the Lord by death to separate us.”

Whilst he was a captain in Bombay, George’s son was born in December 1768. He was christened George on 25 April 1769 but sadly died just a few weeks later, on 27 June.

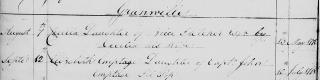

His daughter Elizabeth was born on 10 July 1776 and her christening was held on board the ship Granville. Her father was noted as Captain John [sic] Emptage.

Whereas other entries in the christening records refer to the father of the child and his wife, those for baby George and Elizabeth make no reference to George’ wife or their mother. In his will, George refers to Elizabeth as his natural daughter, indicating that she was illegitimate.

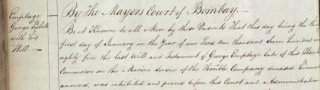

George Emptage died on 20 January 1785. Probate was granted by The Mayors Court of Bombay at the Town Hall on 7 February, with two of the Executors, Robert Jackson, a Lieutenant Colonel in the military service of the Honourable Company and Nicholas Penny, a Captain in the marine service of the said company, being sworn to discharge any debts George may have had and to make a full inventory of his Goods Chattels Rights and Credits and to render a true and just account before 7 February 1786. The Court reserved the right to grant administration to the other three executors, one of whom was Thomas Bailey, George’s brother in-law.

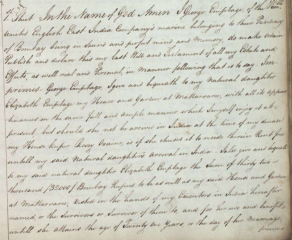

In the Name of God Amen I George Emptage, of the Honourable united English East India Company’s marine belonging to their Presidency of Bombay being in sound and perfect mind and memory, do make ordain publish and declare this my last Will and Testament of all my Estate and Effects, as well real and Personal, in Manner following that is to say.. Imprimis George Emptage, I give and bequeath to my natural daughter Elizabeth Emptage my House and Garden at Matharvaru, with all its appurtenances in the same full and ample manner which I myself enjoy at present, but should she not be arrived in India at the time of my decease my housekeeper Rosy Oxaine, is if she chuses it to reside therein rent free untill my said natural daughter’s arrival in India.”

In addition, George bequeaths to Elizabeth 32,000 Bombay Rupees, vested in the hands of his executors, for her use and benefit until she attains the age of twenty one years or the day of her marriage provided that the marriage is by and with the consent of her [unnamed] mother. The property and money are to remain with Elizabeth for her use and benefit during the term of her natural life and to be at her sole disposal, whether married or not, to be bequeathed by her will.

To his housekeeper, Rosy Oxaine, George bequeaths 20,000 Bombay rupees, to be invested by his executors for the rest of her natural life, the interest to be paid to her annually at least. After her demise, the remaining principle sum is to be transferred to his natural daughter Elizabeth.

George makes a bequest of 10,000 rupees to Ann (Nancy) Procter, the daughter of his housekeeper by the late Captain Procter. He refers to the marriage of the daughter, with the consent of her mother.

In case of the demise of Elizabeth before she reaches twenty one or before marriage, George directs that the house and gardens be the property of his Housekeeper Rosy Oxaine until her demise and that they should then pass to Rosy Oxaine’s daughter Ann Procter. George bequeathed 8,000 rupees to John, the son of the aforesaid Captain David Procter.

There are several small bequests to friends and their wives, often a sum of money to buy a ring.

George made provision for the slaves in his household. Some are noted as the property of his housekeeper, one as belonging to John Proctor. Of the others, the boy Hector is the property of Elizabeth, having been a present from Captain Alexander Jameson. George bequeathed a named girl and boy to Elizabeth with the instruction that they were not to be sold but, at the time of her death or before if she chooses, they should be given their freedom. He gave the remainder of his named slaves their freedom and 50 rupees each.

To Elizabeth, he bequeaths a silver coffee pot and salver which he won in a raffle or lottery in 1779. To Ann Procter he leaves one dozen silver teaspoons. To his housekeeper, Rosy Oxaine, he leaves such other of his household furniture and plate as she may choose. All the rest of his Effects together with his house in town are to be disposed of to the best advantage.

After all the above Legacies and Bequests are paid and satisfied, George wills and bequeaths the rest and residue of his estate, whatever it may amount to or whatever it may be composed of, to his dearly beloved sister Mary Bailey. Should she have predeceased him, it is to go to her heirs. Should she have no issue, one fourth part of the amount is bequeathed to his dearly beloved brother in-law, Thomas Bailey, with the remainder to Elizabeth.

The will was signed, sealed and dated in Bombay on 9 June 1784.

George made frequent reference to his natural daughter Elizabeth but the only reference to Elizabeth’s mother was to Elizabeth needing her consent to marriage. Unfortunately he did not name the mother but evidently it was assumed that she was known to the the executors and trustees.

He made the same reference to Ann Proctor, requiring that she too had the consent of her mother to her marriage. In this case, the mother was Rosy Oxaine, the father was the late Captain Procter.

Elizabeth was only six when George wrote his will. Evidently he wished to provide a stable home for her and by allowing his housekeeper to remain there for her lifetime, and with the necessary income to ensure that she didn’t need to take a job elsewhere, he did just that.

If Elizabeth died before she reached twenty one or married, the house and garden should be the property of Rosy Oxaine until her demise and then pass to her daughter Ann Procter.

This seems an extraordinarily generous bequest to his housekeeper and her daughter. We have to ask ourselves as to whether it is indicative of the fact that Rosy Oxaine was more than just a housekeeper to George and that she was in fact Elizabeth’s mother. And that this was therefore known to his executors.

Elizabeth Emptage married Richard Hall Gower on 6 May 1802 in Hertford. The marriage was noted in the Gentleman’s Magazine and Historical Chronicle for the year MDCCCII, Volume LXXII, Part the Second, in the section ‘Marriages of remarkable Persons’. (1802)

At Hertford , Richard Hall Gower, esq. of Cheshunt, to Miss Emptage, daughter of the late Commodore E. in the East India Company’s service.”

“The Annual Register or a View of the History, Politics and Literature of the Year 1833” contained an extensive obituary for Richard, who died that year.

Following the death of his father, a clergyman and physician of eminence, Richard, in 1781, aged just thirteen, entered the service of the East India Company, as a midshipman, on board the Essex. On his first voyage, the ship was employed to convey troops to India and called at Bombay.

Midshipmen’s duties often included taking messages between ships or between ship and shore. George was already Commodore by the time Richard arrived and it is highly likely that they met during the course of their service.

Given the nature of the Honourable Company in Bombay, in addition to day to day service contact, there would have been official functions and society events. And so it is quite possible that Richard and Elizabeth met during that period.

Elizabeth was just nine years old when her father died in 1785 but her home was in Bombay and it is likely that she continued to meet Richard at events when he was in port. She married Richard seventeen years later, when she was twenty six.

As a midshipman in the East India Company, Richard “became one of the brightest ornaments of that service. In that ship he soon attained the knowledge of seamanship, which led, in more mature life, to the production of a work entitled “A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Seamanship”, which has not been surpassed by any other on the subject.”

He was much connected with sailing and designed ships, yachts and naval equipment, conducted many naval experiments and brought about many naval improvements. But Richard also experienced many disappointments and losses in his experimental career and, having become the father of a large family, decided to devote his time and energy to their education.

It is thought that, from his own childhood experience, Richard had an abhorrence of public schools and so “From this time”, he wrote in a letter to a friend, “I ceased to follow my naval experiments, and became almost as one who had never know salt water; my time being occupied by the instruction of my children in a way peculiar to myself.” He added that they were the best spent and most happy days of his existence.

Regardless of his experimental disappointments, as his life drew to a close, Richard Gower had the gratification of “seeing many of his inventions and improvements in naval architecture brought into practice.”

Richard and Elizabeth had settled in Cheshunt but, in 1817, they moved to the Nova Scotia estate in Ipswich, Suffolk, a town which Richard knew from his days at school. It was a busy port on the river Orwell with docks and shipbuilders and the house was close to the river, with gardens leading down to the river. So, whilst Richard may have described himself as no longer having anything to do with salt water, he chose to live within sight and sound of ships.

Indeed, the largest ever East Indiaman, the Orwell, was launched from those shipyards in 1817. It was an impressive ship of 1350 tons, with a keel length of 153 feet, one of the largest of her class to sail from an English port. 2000 loads of Suffolk oak went into her sturdy hull and she was completed in 15 months. I rather hope that Richard was in Ipswich by then to see it and I wonder whether any of his designs had been incorporated.

Richard died in Ipswich in 1833 aged 65 and Elizabeth died in 1840, also aged 65. Both were interred at the church of St Mary at Stoke, Ipswich, Suffolk, a church within a few minutes walk of the river and the docks. And so Richard lies in the company of Master Mariners, shipwrights and men of the sea.

Richard and Elizabeth had eight children: Mary Ann, Richard, Elizabeth, Charles Foote, Sarah Rozanne, George (who died in infancy) and Caroline, all born in Cheshunt, and Charlotte, born in Ipswich.

Confirmation of the relationship between Elizabeth and George came from the will of George’s sister, Mary Bailey, who died in 1807. In her will she referred to her niece, Elizabeth Gower.

Susan Morris and Michele Martin-Taylor

Personal note from Susan: Both Calcutta and Bombay feature in my paternal family history. My father was born in Calcutta, the son of a British merchant and manager of the leading departmental store. Whenever the family returned to England for visits, they did so from Bombay, which was still a very important port city in the mid 20th century.

Bombay is now known as Mumbai and Calcutta as Kolkata (derived from the local Bengali name of Kolikata).

And, for several years, I drove past the church of St Mary at Stoke, Ipswich on my daily commute to work. It’s a pity that I didn’t know then of the Emptage connection. Perhaps I could have found Elizabeth’s grave.

Sources

Company rule in India – maps

Armies of the East India Company 1750 – 1850

Google Books: Reports from the committees of the House of Commons

British Library: Report from Commodore George Emptage to the Bombay Council, 13th June 1783

Google Books: The History of the Indian Navy 1613 – 1863

Google Books: Gentleman’s Magazine and Historical Chronicle for the year MDCCCII, Volume LXXII, Part the Second

Google Books: The Annual Register or a View of the History, Politics and Literature of the Year 1833

History of the Indian Navy, Establishment of the Bombay Marine

“Sahib the British Soldier in India” by Richard Harris, by HarperCollinsPublishers