John Emptage/Emtage – convicted at the Old Bailey for stealing a tea chest

Let’s step back 270 years and try to understand what did actually happen to John Emptage/Emtage who was convicted at the Old Bailey on the 11 September 1745…….

John Emptage was indicted for stealing a mahogany tea chest, with three canisters belonging to Nathaniel Marsh, valued, 4 s. on 7 August 1745. He was charged with theft and appeared at the Old Bailey, London on 11 September 1745. In the trial transcripts:

Mr. Marsh said he missed a tea chest out of his shop, but could not swear it was his property, because he bought it ready made.

The Prosecutor’s maid servant said she saw the Prisoner take the tea chest out of the shop, and go away with it.

Joseph Cashier deposed that Mr. Marsh’s maid cried out, Mr. Cashier, a thief, and he saw the Prisoner run along, that another man offered to stop him, and the Prisoner said if he stopped him, he would swear a robbery against him; so the man did not stop him. But he was pursued and taken. He proved it to be Mr. Marsh’s property.”

John Emptage was found guilty and sentenced to be transported for 7 years1.

After being convicted at the Old Bailey, John was incarcerated in Newgate Prison, once the most notorious prison in London. Famed for its dark squalor, overcrowded, lice-ridden dungeons and sadistic keepers, Newgate Prison served as the gateway and portal to the gallows.

It was, almost from its beginning, an emblem of death and suffering… a legendary place, where the very stones were considered ‘deathlike’…it became associated with hell, and its smell permeated the streets and houses beside it.”2

From 1615 onwards, transportation had became increasingly common, and initially most people were transported to North America or the West Indies. However, from 1718 onwards, transportation was entirely to North America. The period of transportation was usually 14 years for those receiving conditional pardons from death sentences and seven years for non-capital offences3.

Captain James Dobbins, Master of the Plain Dealer, was well known in the trade of transporting convicts. He had made his first trip to Maryland with convicts in 1744 and made a further eight voyages prior to his voyage in January 1746 taking male and female prisoners from Newgate Prison to Maryland. However, pirates, privateers, and hostile navies could also threaten voyages and the Atlantic was full of vessels either acting alone or sanctioned by enemy states looking for other boats to seize and plunder. Convict ships were not immune to such threats.

John Emtage, listed on the manifest for transportation, departed England, in January 1746, on board the convict ship Plain Dealer with Captain James Dobbins, bound for Maryland4. It is reported that Captain Dobbins was involved in one of the most remarkable incidents of convict transportation, when on February 21, 1746, his ship the Plain Dealer was overhauled by the Zephyre,

a French Man of War of 30 Carriage Guns and 350 Men.” Turning the convicts loose, Dobbins fought an engagement “of two Hours and a Half, in which forty of the Convicts on Board behav’d well, and fought with great Courage.”

Nevertheless they were overpowered, and the Frenchmen took Dobbins and a few of his passengers (convicts) on board the man-of-war, leaving a prize crew on the Plain Dealer with most of the convicts. Dobbins soon got back safely to England, but the Plain Dealer was lost on the coast near Brest with everyone on board save seven Frenchmen.

The Plain Dealer incident on 21 February 1746 is reported in numerous books on the subject of north Atlantic convict transportation5 as it was widely reported in the newspapers at home. Captain James Dobbins himself filed a report in the form of a letter, dated 7 March, from Port-Louis, France, which was reproduced in part in the London Evening Post, 25-27 March 17466.

The War of the Austrian Succession (1740-1748), which was in full-swing at the time and the reason why the Plain Dealer was captured by a French warship in the first place, may well have been a contributory disruptive factor as to why little is known about the fate of the prisoners from the Plain Dealer7. That said, Captain James Dobbins was Master of the ship George William transporting felons from London to Virginia in January 1747, one year later8.

As early in the War of the Austrian Succession as 1744, prisoners were mounting on both sides of the English Channel and the French were enthusiastic about Britain’s proposal to exchange detainees. However the Admiralty would not consider anything but a ‘man-for-man’ agreement, being confident that French captures would be out-numbered even more heavily than in the previous war between the two nations. Their Lordships at the Admiralty realised that it was well worth the expense of keeping the surplus French prisoners on British soil for the sake of depriving the enemy of their services9.

Although there had previously been exchanges of prisoners between Britain and France10, by the summer of 1745, a formal agreement had been drawn up between these two nations, using the Dutch Ambassador to France, Abraham Van Hoey, as an intermediary11. The exchange of prisoners-of-war however, was not without its problems. For example, in October 1745 the Admiralty suspended exchanges because the French owed about 2000 men12.

However records show that thousands of prisoners were exchanged and while the numbers were carefully recorded by The Commissioners for taking Care of Sick and Wounded Seamen and for the Care and Treatment of Prisoners of War13, unfortunately the names of the prisoners do not appear to have been recorded.

The Cartel that the Admiralty drew up stipulated that:

‘The Exchange of Prisoners shall be made Man for Man, according to their Qualitys (rank) as is mentioned in the first Article; but it may happen … that they cannot be exchanged for an Equal Quality, their Exchange shall nevertheless take place, and it is agreed, in default of a real Exchange, that they shall reckon, viz; A Captain of a Man of War for ten Men; A first Lieutenant for Six Men … The Passengers shall be exchanged against other Passengers, and in Case there are any of distinction, who cannot be exchanged for equal Rank, The Number of Men to be given for such Passengers shall be agreed on, by one Side and the other14.”

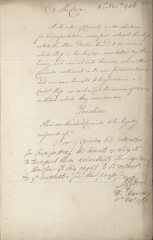

Captain Dobbins was undoubtedly one of the men exchanged in 1746. As for his passengers, or convicts, the ruling signed by D. Ryden and W. Murrey indicates that the prisoners that survived the Plain Dealer incident, were indeed exchanged for French prisoners.

In a question to the Navy Board on the 8 November 1746, it was stated that:

A number of convicts under sentence for transportation were put on board the ship called the Plain Dealer bound to America, which ship in her voyage was taken by the Enemy and carried into France, where the Convicts continued in Prison for some time, and are now brought to England in a Cartel Ship15 as exchanged Prisoners of War, on board which they now remain.

‘Question. How are the said Convicts to be legally disposed of?’

In their ruling, D. Ryden and W.Murrey16 stated that:

‘We are of opinion, the contractor for transporting the convicts is obliged to transport them notwithstanding the capture and therefore they ought to be delivered to said contractor for that purpose’.

From this we can deduce that, assuming that John Emtage was not killed during the fight on board the ship, and was not on the Plain Dealer when it was lost off Brest, then in all probability, John was exchanged under the terms of the Cartel, his status as a convict, or ‘Passenger’, being taken into account when the exchange took place.

So who was John Emptage/Emtage, convicted at the Old Bailey on 11th September 1745 and sentenced to 7 years transportation…….well that’s another story!

My thanks to John Graves, Curator of Ship History at the National Maritime Museum, who provided some of the background information relating to the Admiralty.

Michele Martin-Taylor

Notes

1. Old Bailey Proceedings Online John Emptage, Theft > grand larceny, 11th September 1745. Reference Number: t17450911-41. Offence: Theft > grand larceny. Verdict: Guilty. Punishment: Transportation

2. Newgate Prison by Peter Ackroyd, taken from ‘London, The Biography’

3. http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/records/research-guides/transportation

4. Emtage, John. Sentenced Jun-Dec 1745. Transported Plain Dealer Jan 1746. Middlesex More Emigrants in Bondage 1614-1775

5. Smith, Abbott Emerson Colonists in Bondage: White Servitude and Convict Labor in America 1607-1776: University of North Carolina Press (1947).

6. The Gentleman’s Magazine 1746 Vol 16 page 181 – issue 2869 searchable for example in the 17th-18th Century Burney Collection Newspapers Archive

7. For background information to the War see Anderson, M S The War of Austrian Succession: Routledge (2014).

8. The King’s Passengers to Maryland and Virginia by Peter Wilson Coldham 2006

9. Anderson, Olive The Establishment of British Naval Supremacy at Sea and the Exchange of Naval Prisoners of War: English Historical Review 75 (1960) pp77-89

10. General Account of Exchanges of Prisoners of War between England and France, 13 February 1745 The National Archives: SP42/30/47

11. The National Archives: SP 78/230/201,212,217,220 etc.

12. The National Archives: SP 42/29/303

13. The National Archives: SP 42/30/49

14. The National Archives: SP 42/30/123

15. Ships employed on humanitarian voyages, in particular, to carry prisoners for exchange between places agreed upon in the terms of the exchange. While serving as a cartel, a ship was not subject to capture.

16. ADM 7/298 The ruling signed by D. Ryden and W.Murrey, 8 November 1746; Adm 7/298

Images:

Tea chest at the V&A showing the space for three cannisters