As we start considering the life of Walter, we immediately have a problem. How was his middle name spelt?

There was little consistency in spelling and various people would, over time, spell it in the way they thought they heard it or thought it should be spelt.

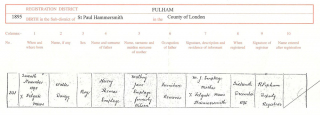

1895 birth certificate: Walter Danzy

1901 census: Walter

1911 census: Walter Danzy (though his step father stumbled over the spelling)

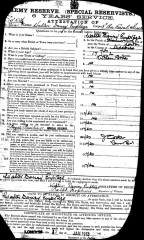

1913 joined the army: Walter Dansy Emptage – his own signature

Other military records: Walter Dansy and Walter Danzy

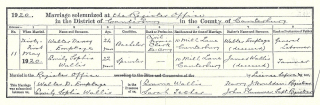

1920 marriage certificate: Walter Dansy Emptage named but signed as Walter D. Emptage

When there is the option of an s or a z, I’ve always preferred to use an s and so I’m inclined towards the marriage certificate spelling and his signature on the form when he joined the army. In general terms, I will refer to him as Walter Dansy.

Unfortunately there were also wide variations in the spelling of Walter’s mothers name, Malbry Jane Emptage, which didn’t help the research. I tend to favour the spelling Malbry as I first saw it spelt on Walter’s birth certificate.

For both of them, when referring to records, I ought to use the spelling as per the records, so I beg your forgiveness for apparent inconsistencies in the writing of our story.

Walter Danzy Emptage was born on 7 November 1895, at 7 Felgate Mews, Hammersmith, London. His father’s name was Henry Thomas Emptage and his mother was Malbry Jane Emptage, formerly Wilson. Henry’s occupation was furniture remover.

Henry and Malbry had five children born between 1889 and 1895: Alfred George, Charles Frederick (Charley) and Edward Lindsey (who were twins), Helen Lucy [Nell] and Walter Dansy.

According to family lore, Henry Thomas had been working for a furniture removals firm in Hammersmith when, in 1896, he and his workmates had been moving a piano from the third floor of a building. They decided to take it out through a window. The rope broke and the piano fell on Henry Thomas, killing him outright.

However, the death certificate says that he had suffered pleurisy [an infection around the lung] for eleven days and ‘congestion of the lungs for two days’. Malbry Jane Emptage, ‘widow of the deceased’, had been present at his death and his occupation was indeed ‘furniture remover’s carman’ which means that he drove the horse drawn remover’s cart.

It is clear that Henry Thomas did not die outright as a result of the piano falling on him but it is quite likely that he was badly injured. In those days, people were kept in bed too long and often contracted pneumonia which led to pleurisy.

When Henry died, the eldest child was seven and the youngest child, my grandfather, Walter Dansy, was just one year old. There were no state benefits then to keep the family going. Walter’s brother Edward Lindsey told his son David that Malbry and the children had been left in abject poverty by the death of Henry Thomas Emptage.

It seems that Henry Thomas was most probably working for Malbry’s brother Danzy Sheen Wilson, who was a self employed furniture remover in the area and evidently the person after whom Malbry and Henry named their son. I hope that Danzy Sheen Wilson helped to look after his sister and her children after Thomas died.

The 1901 census shows Malbry Emptage with all the children apart from Alfred, who was away at an Industrial School in Macclesfield, being taught a trade as a shoe maker. Malbry was 31, had been a widow for five years and was ‘living on her own means’. Charles and Edward were 8, Helen was 7 and Walter was 5.

In 1902 Malbry married Ernest Deamer, a coachman and in 1911 they were living at 88 Dorset Street, South Lambeth. Ernest Deamer was aged 40, a waiter at Wellington Barracks in London. They had been married nine years and had no children of their own.

Walter Danzy was a fifteen year old factory hand, the only one of Malbry and Henry Thomas’ children still living at home with his mother.

Indeed, there would have been no room for anyone else as the dwelling was reported as having just two rooms including the kitchen. It may have been a couple of rooms in a shared house with a toilet out the back shared by several residents in the building. The whole street has since been redeveloped with post war or more recently built blocks of flats.

Army Service and the First World War

Both of Walter’s brothers had joined the army in 1909 when they were seventeen. Edward Lindsey had joined the Royal Engineers and Charles Frederick had joined the Buffs, the East Kent Regiment.

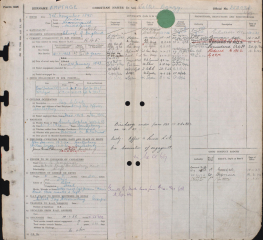

When Walter, by then a kitchen porter, reached seventeen, he too joined the army. In January 1913 he enlisted in the Royal Fusiliers Special Reserve as a clerk.

He was said to be 5′ 4½ inches tall, weighed 112 lbs, with good physical development. He had blue eyes and light brown hair.

His next of kin were given as: mother Malbry Jane Deamer, initially at an address in Lambeth and then at 23 Alma St, Canterbury, and his brothers Edward (Royal Engineers) and Charles (East Kent Regiment).

Did they all join up for a career in the army as a way of escaping the poverty in which they lived?

They would have received three full meals a day, a roof over their heads and expected to see something of the world.

But, when war broke out in 1914, everything changed. As trained soldiers, Walter and his brothers were some of the earliest members of the army into battle, with Walter landing in France on 23 November 1914.

The first use of gas on the Western front was by the Germans when they released 5,700 canisters containing 168 tons of chlorine gas near the Belgian city of Ypres in April 1915. The gas settled in the four miles of trenches occupied by 10,000 Allied troops. Half of them died of asphyxiation within ten minutes of the gas reaching the front line. The rest were temporarily blinded and stumbled around in confusion, coughing heavily. 2,000 were captured as prisoners of war.

In panic, the remaining Allied troops fled towards Ypres, which was then subjected to heavy bombardment by the Germans until the end of 1915. By the end of the war, Ypres had been reduced to piles of rubble.

Was Walter in the trenches in that gas attack? Was he gassed? Was he in Ypres through the months of sustained bombardment?

Did Walter take part in the attack on Sanctuary Wood in September 1915, thus sustaining his shell wound on 27 September 1915? Ironically, Sanctuary Wood was originally known as Hill (Ridge) 62 but had been given the name Sanctuary Wood in October 1914 because it was silent and peaceful. After the battle, someone who won the Military Cross at Ypres described Sanctuary Wood in a letter as “The dearest and most dreadful spot in the whole of that desolation of abomination called the firing line”.

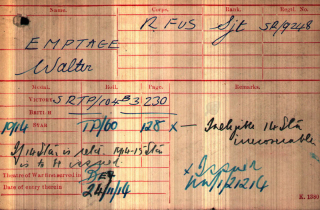

The records show that Walter was in France from 23 November 1914. He was wounded at Ypres on 27th September 1915 with a shell wound in the shoulder and transferred to the Richmond War Hospital in Dublin from 4 October 1915 to 10 January 1916.

[The hospital had previously been a district asylum but, like many asylums, had been turned over to the army to care for wounded soldiers.]

After he was discharged from the hospital in Dublin he remained in the UK. In August 1916, at Hythe, Walter qualified as a 2nd class instructor both in musketry and the mechanism of the Lewis Gun.

Walter returned to France in December 1916. He was given two weeks leave to the UK on 5 December 1917 but was then returned to France. He received a gun shot wound in his buttock in January but remained there until April 1918 when he was brought back to England with another wound, to his right arm and right side. He was hospitalised for 77 days until July 1918. He remained in the UK until he was demobbed in March 1919.

In 1918 Walter contracted gonorrhoea. He spent eight days in hospital from 6 November 1918 before being transferred to the Cherry Hinton Military hospital, Cambridge where he stayed for 51 days, being discharged on 3 January 1919. He was 23 and unmarried.

Note: Unfortunately, venereal disease was almost an occupational hazard for young soldiers in the first World War. Roughly 5% of all the men who enlisted during the war became infected. In 1918, there were 60,099 hospitals admissions for VD in France and Flanders alone. By contrast, only 74,711 cases of ‘Trench Foot’ were treated in hospitals in France and Flanders during the whole of the war.

Whilst almost never fatal, venereal cases required on average, a month of intensive hospital treatment. The greatest number of venereal patients in hospital at any one time in 1918 was estimated to be 11,000, enough men to supply the effectives (soldiers fit and able for service) of a division.

Source: http://ww1centenary.oucs.ox.ac.uk/

Walter was promoted to Corporal in 1917 and to Sergeant shortly afterwards. He was demobbed after 6 years and 57 days service, transferring from the 5th Battalion, Royal Fusiliers to the army reserve on 14 March 1919.

The Medal Roll indicates that he was awarded the Victory medal but that there was some confusion as to whether he was eligible for the 1914 Star or the 1914-1915 Star. The 1914 Star seems to have been issued by mistake.

His discharge address was given as St Margaret’s St, Canterbury. (His mother, originally from the Bridge district, near Canterbury, had moved to Canterbury from London after Walter had enlisted).

The report of his medical in February 1919 described his main wounds and reported that there was some loss of muscle below the right scapula but no disability from the wound in the right arm. Overall, his disability was considered less than twenty per cent.

However, given what we now understand about the mental affects of the war and about shell shock, we must wonder what long term effect it had on Walter. On top of his own experiences, his brother Charles Frederick had been killed. Was he suffering from what we know as Post Traumatic Stress Disorder? If so, could that and his childhood poverty have contributed to his later action?

Marriage and children

Walter Dansy Emptage and Emily Sophia Wallis married on 31 May 1920 in Canterbury.

As shown in Emily’s story, she had known Walter’s sister Helen and brother Edward at least from the summer of 1917 but we don’t know whether she met them through Walter or met Walter through them.

Walter was 24 and Emily was 22. Both their fathers were deceased and Walter gave his father’s name as Walter, a general labourer.

As we know, his birth certificate gave his father’s name as Henry Thomas Emptage. Why the discrepancy?

Walter had been just one year old when his father died and he would have had no memories of him. Given the social mores of the day, was his father ever mentioned again? Or, if he was spoken about, was he actually named or just referred to as ‘your father’ as parents do when talking to children?

When completing the administrative details for his wedding, Walter evidently didn’t know his father’s name and Malbry, though still alive, wasn’t there to ask. So Walter’s own name appears on the marriage certificate as his father’s.

His brother Edward Lindsey married twice and each time gave the wrong but different names for his father.

Initially I found this all rather confusing but it seems that this was a regular occurrence for people whose parents had died when they themselves were young or had been brought up without knowing their father. They either gave their own name as the father’s name or another name.

Walter and Emily’s first child was born the same year as the marriage and the youngest of their twelve children was born in 1939. One of the children died just a year old but the other eleven survived:

| 1920 | Joan, | 1927 | Allan, | 1933 | Brenda, | 1936 | John |

| 1921 | Eileen, | 1929 | Hazel, | 1933 | Stella, | 1938 | Jill |

| 1923–24 | James, | 1931 | Ena, | 1934 | Anthony, | 1939 | Colin |

It puzzled me that the children appeared quite regularly, apart from a gap between James’ birth in 1923 and Allan’s in 1927.

Service in Palestine

Walter had become a civilian pay clerk in the army pay office in Canterbury after being demobbed in March 1919.

But, on 15 January 1923, he joined the RAF and was posted to the RAF depot in Uxbridge. He was 27 years and 69 days old when he enlisted, becoming a pay clerk in Accounting, Group 4.

On 19 January 1923 he was with the 14th Squadron and posted to Palestine.

Walter enlisted as an AC2 (aircraftman 2nd class) but was promoted a day later to Corporal. He was reduced to AC2 again in June 1924. Whatever he did to be demoted, he was deprived of a badge at the same time but it was restored in March 1925 though I don’t think his rank was restored.

He was hospitalised in Palestine General Hospital for ten days in October 1923 but there is no indication whether this was through injury or illness.

Walter served for four years, discharged on 14 January 1927 under Kings Regulations and Air Council Instructions para 593 (1). (KR and ACI) [Unfortunately I can't find references for that particular paragraph anywhere.]

On enlistment, Walter was 5’8″, fair haired, blue eyed and of fresh complexion. He had a tattoo on his left forearm of a man's head and vaccination marks on his left. No note was made of any wounds or scars at enlistment.

He seems to have grown 3½ inches between joining the army aged 17 and joining the RAF when he was 28. His home life was one of abject poverty so I assume that the better food which he’d have had in the army contributed to him growing several inches.

The family was still living at 10 Mill Lane, where Walter and Emily lived when they got married and where the children were born.

The enlistment record shows he was married to Emily Sophia and had two children: Joan Francis born 19.7.20, Eileen Joyce born 17.11.21 and, added later, James Ernest Dansy, born 30.7.23. So, assuming it was a normal pregnancy, Emily was about ten weeks pregnant when Walter enlisted and he wasn’t home when James died.

I wonder if James’second name of Ernest was named after Walter’s stepfather, Ernest Deamer? I hope it is a sign that his step father was kind to Walter.

Walter’s service in Palestine begs some questions: did Walter run away from home and enlist when he knew his wife was pregnant for the third time? Was it a way of providing more money? Would the salary of an enlisted RAF pay clerk be any different to that of a civilian pay clerk with the army? Or was he a man who was simply happier in a military environment?

As a civilian pay clerk with the army, Walter probably had access to all sorts of news. He probably knew that the RAF, which had been run down after the war (whilst it fought to be a separate military force and not be absorbed into the army and navy) was, in 1923, to be built up again because it had won its fights with the government. New units would need new administrative staff.

He may have known about the 14th Squadron in Palestine. I wonder if he chose to be sent there?

Being in the RAF from 1923 to Jan 1927 would explain why Alan, the next baby after James, wasn’t born until 1927. I don’t know Allan’s date of birth but he must have been born any time from halfway through August to December as his birth is registered October – December 1927. Walter was on leave from 18 November 1926. My guess is that Emily got pregnant almost immediately he arrived home.

Note: Palestine was a British protectorate from 1923, under the auspices of the League of Nation, until May 1948.

Second World War

As a child I understood that Walter had been in the army during the Second World War. But, when I began researching the family history I realised that he would have been 44 when war broke out in 1939.

In September 1939, conscription was limited to men up to age 41 but by 1942 all male subjects between 18 and 51 years old were liable to be called up. Men could be rejected for medical reasons and were not eligible if they worked in reserved occupations.

The records of those who served in the forces during the Second World War are still classified by the Ministry of Defence and can only be accessed by application by the next of kin so I’m unable to say whether he enlisted when war broke out, whether he was conscripted or what his war service consisted of. However, once conscripted, he would have had to see out the war, unless he was injured again and invalided out.

Emily and the children moved to Yorkshire during the war as, it is thought, it was where Walter was stationed.

Perhaps there is someone in the family who has rather more information about Walter’s service during World War Two and can let me know.

Walter’s Crime

In 1951, Walter embezzled funds from his employer and the Yorkshire Post carried a report on 7 November 1951:

Three years for £532 cheque forger

Walter Danzey Emptage (55) accountant, Knowle Mansion, Baildon, said to be married with 11 children, was sent to prison for three years at Leeds Assizes today for forging cheques.

Mr J B Wallis, prosecuting, said that Emptage had been employed by Fox Rutherford and Co., Mabgate, Leeds, and had been secretary of three other companies. He obtained £532 18s 6d over the period from December 1950 to July this year by forged cheques.

Emptage asked for 18 other offences to be considered, including one of attempted suicide.

Mr E Ould (defending) said that Emptage had three periods of military service and had been wounded five times. He joined the prosecuting firm in 1948. Seven of his 11 children were living at home and he found himself very hard up. Very foolishly he took one or two small sums at the beginning and, when he tried to pay them back, started gambling.

Lord Goddard, sentencing Emptage, said “this is a lamentable case and you knew perfectly well you would have to be punished.”

Knowle (or Knoll) Mansion was a large Victorian gothic style building set in lovely grounds. The house had been sold to the Baildon Urban District Council and converted in to flats to house local people. It was demolished in the 1960s and new flats built there.

Some time in the late 1950s Walter and Emily separated. As the divorce index only goes up to 1903 I don’t know whether they divorced.

Emily died in 1961 and in 1974 Walter married Mary A Gannon in Surrey Northern district, when he would have been 79, four years before he died in the same district.

Susan Morris

6 June 2015