Born in Margate on 15th February 1830, William Henry was the son of William Emptage and Elizabeth Peters. William snr was a mariner and had been a coxswain on the lifeboats off the Kent coast between Broadstairs and Margate.

He was one of those who lost their life on the 5th January 1857 during the rescue attempt of the ‘Northern Belle’ and the loss of the lugger ‘Victory’. Read the article here

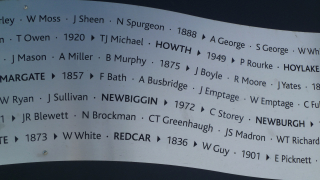

William Emptage’s death and that of his nephew John Emptage is recorded on the RNLI memorial in Poole, Dorset.

William Henry Emptage joined the East India Company, becoming an Able Bodied Seaman, sailing between England and India.

In 1851 he signed on with the Hudson Bay Company and sailed on the company’s barque ‘Norman Morison’ which was making its second voyage from England to north west America where it had established a fur trading post.

A long and perilous voyage

Originally built from teak for the East India Company in 1846, the ship had been brought by the HBC in 1848. The first immigrants to Vancouver Island (in what would later become Canada) sailed on the ship. It was a fast ship; on its first voyage, 1849-50, it cut a whole month off the normal six month voyage between England and the west coast of North America.

The third voyage began in 16 August 1852 at Gravesend, Kent, arriving at its destination on 16 January 1853. The ship carried some 146 passengers, adults and children, families who had signed up to work for the HBC and to settle in the area where it had established a trading post. They were leaving a country deep in agricultural recession and were anticipating a new life with more chance of earning a decent income. They were heading for the area which would become known as the colony of British Columbia in Canada.

The voyage took several months during which there were both births and deaths on board. They sailed through the North and South Atlantic Oceans, through the highly dangerous seas around Cape Horn at the southern most point of America, and then turned north through the Pacific Ocean, following the coast of south and then north America. Finally they arrived at their destination, Victoria. There was always the risk of straying too far off course, too far south into the ice of Antartica.

It was the last voyage made by the ‘Norman Morison’ for the HBC before it returned to London to be sold.

Life changing injury

Coinciding with William’s arrival in Victoria two years earlier were reports that gold had been discovered by Indians on the Queen Charlotte Islands. A party of men from the ship was sent to investigate, including William.

Presumably the men found evidence or indications of gold because, whilst they were rock blasting, an explosive went off prematurely. Badly injured, William was taken back to Victoria where the doctor decided that his left hand needed amputating above the wrist.

With no chloroform for anaesthetic, the doctor gave him whiskey and put a rock in his mouth to clamp down on, so that he wouldn’t bite through his tongue during the operation. In a second operation, the doctor peeled the skin back to the bone and then cut the bone a second time, one inch shorter.

When the accident happened, William was in his early twenties. It could have been the end of everything for him but, despite the loss of his forearm, when the injury finally healed William was still able to make use of his arm, able to carry a milk pail in the crook of his arm.

Jack Tar with one arm

It’s not known whether he had intended to stay in the country or to continue his sailing career with the Hudson Bay Company but the amputation of his forearm meant that he could no longer be a sailor. Although referred to as a “Jack Tar with one arm” he proved to be able, not only acting as an interpreter but, following his recovery at Fort Simpson, he worked on the large HBC farm at Fort Langley from 1856 to 1859 until it was leased to two English adventurers.

When they took over, William left the farm to settle on his own account but unfortunately, having got the most out of it for three years, the two men disappeared, leaving the farm in a wretched state.

In 1864 the HBC appointed a highly experienced company man with the official title of Clerk, Ovid Allard, to bring the farm back to life. Ovid Allard rehired William and gave him the job of caring for the cows and horses around the fort and for weeding the neglected garden.

William helped Allard bring the farm back into cultivation, supplying the miners who moved to the area in the Gold Rush of the 1860s. Indian women were employed on the farm at 25 cents a day, to do the hoeing. Eventually the farm became unprofitable after the end of the Gold Rush and the customers went away.

On December 12th 1870 William pre-empted 160 acres at Langley Prairie. The details of The Pre-emption Acts varied over the years but initially allowed land to brought with half paid in cash and the balance paid two years or so later. William must have been confident of his ability to work the land and make it pay.

In 1873, as the settlement grew around Langley, he and 28 other landowners petitioned Victoria for Langley’s incorporation as a municipality.

Maps show that by 1884 William owned a plot adjoining the Langley Farm. The western portion of that property is now occupied by the Trinity Western University.

William began a relationship with the daughter of Mooseem Pokia, a Musqueam Chief and began raising a family with her. According to the censuses from 1881, their children were Emily (born c1861), William jnr (born 1864), Edwin (born c1869) and Stephen (born c1872). However, hearsay referred to William having two daughters at Fort Langley so perhaps there was another daughter.

William and Louisa formally married on May 27th 1875. The ceremony was conducted by catholic priests and they gave her the name of Louisa.

The 1881 and 1891 censuses record William as a farmer in New Westminster, British Columbia. William was still farming in 1901 though widowed and living with his son William. His son Stephen, also a farmer, lived next door, with his wife Christina and children Maud, Sarah and Stephen.

A love story

Although William and Louisa’s marriage is reputed to have been an arranged one, the story is that it was built on very strong love. And when Louisa died in 1891 and was buried in Fort Langley Cemetery, William had her gravestone carved with the image of their hands holding each other.

William died in 1908 aged 77. He is buried at Fort Langley cemetery close to his beloved wife, Louisa.

The Langley Explorer, 12 October 2012, refers to walking tours conducted by Amn Johal, in the dark, around Fort Langley cemetery. The tour “is based on scholarly Fort Langley research, residents’ insights … and notable paranormal encounters!”

“Proceeding to an obelisk marker, we hear about another fort couple. Amn first praises the keenness of William Henry Emptage to live an adventurous life in early British Columbia…and his rebound from the grisly loss of his hand. Afterward, he met, loved and married Louise, a native princess. And upon her death after happy years together, he buried her in style in the cemetery’s front row! At William’s death, friends couldn’t afford an adjacent plot, so bought him one within sight of hers. After a century a light post was installed in the 1970’s obstructing that view. Since then, each wanders alone through morning and evening mists, bewildered…and asking graveside visitors if they’d seen their lost partners.”

A colourful and useful man

Quoted in an article in the British Columbia Historical Quarterly, October 1945, Jason Ovid Allard, the son of Ovid Allard, talking of his life and experiences, referred to William Emptage as “another colourful and useful man, a former sailor, who lost his left arm by a premature explosion in the first gold-rush to Queen Charlotte Islands.”

Bruce McIntyre Watson, a Vancouver, BC-based historian focuses on the fur trade west of the Rocky Mountains. In his book ‘Lives Lived West of the Divide’ he wrote “The loss of a left hand did not stop William Henry Emptage from leading a full settled life.”

Photo courtesy of Fort Langley National Historic Site, Fort Langley, B.C.

With courage, nothing is impossible

These are the words engraved on the RNLI memorial to those who lost their lives at sea whilst endeavouring to save the lives of others.

It is fitting for William Henry Emptage senior and his nephew John Emptage, who lost their lives whilst attempting to rescue people from the ‘Northern Belle’ in 1857.

Surely those words are also fitting for those like William Henry Emptage junior, whose forearm was amputated when he was so young but who went on to live a colourful and useful life as one of Canada’s first pioneers, together with all those who voyaged on the ship ‘Norman Morison’ to start a new life.

David Lindsey Emptage and Susan Morris

Sources

University of British Columbia: Metis Studies

http://www.fortlangley.ca/langley/whemptage.html

http://www.fortlangley.ca/langley/2dchurch.html#bill

http://www.fortlangley.ca/langley/2etelegraph.html

http://archives.twu.ca/Timeline/historyoftheland.html

http://www.gov.mb.ca/chc/archives/hbca/biographical/e/emptage_william_henry.pdf

http://www.telusplanet.net/dgarneau/B.C.7.htm

http://www.langleyexplorer.com/a-haunting-tour-into-the-past-fort-langleys-grave-tales/

http://www.canadianheadstones.com/bc/view.php?id=8927

RNLI memorial photo by Pat Johnson