London Illustrated News

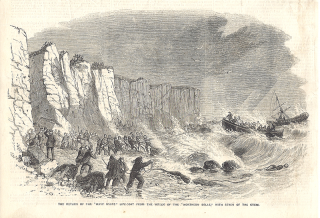

image of the rescue of the Northern Belle

with people watching from the top of the cliff

It was the morning of 5 January 1857 and a large sailing ship, the Northern Belle from America, was in trouble on the rocks. People had gathered on the cliffs to watch events unfolding.

They were watching the Margate men who were out in their luggers attempting the rescue of the 21 crew, the captain and the pilot. The Margate men were joined by two life boats and crew who, unable to launch them into the teeth of the gale, had brought their boats overland from Broadstairs.

It is quite likely that Ann Phoebe Emptage was amongst the crowd, perhaps standing with the other wives, including her sisters in-law. Six members of the Emptage family were out there: her husband Alfred, his brothers George, Charles and Edward, their uncle William and cousin John.

The Margate mariners used the luggers as supply boats to bigger vessels and for fishing, so they knew how to handle the small boats with oars and sails but this was different. In the atrocious January weather – a blizzard raging with high winds, sleet, snow and hail – the watchers knew that the men were in a perilous position.

Ann was not a local girl brought up to familiarity with the sea in all its moods but was born and brought up 20 miles away in Canterbury, where her father, James Hopkins, was a maltster. She was 20 years old when she married Alfred, a fisherman, in 1853 and now, just over three years and two babies later, she was watching him risk his life to save others.

Alfred was the youngest of the nine sons and one daughter of Humphrey and Isabel born between 1816 and 1832. Two of the sons had died in infancy and the others were all mariners, following the family tradition which went back through Alfred’s parents, his grandparents Henry Emptage and Susanna le Brush to his great grandparents Humphrey Emptage and Catherine Pearce.

Sadly, Isabel had died the year after Alfred was born, so Ann had no mother in-law to teach her the duties of a wife of a local mariner and fisherman. Hopefully her older sisters in-law helped and encouraged her but, just three years after she had married Alfred, she must have found herself living a nightmare.

Everybody knew that none of the men who took part in the rescue did so with thoughts of glory or reward in their mind. They were mariners. They lived by the sea, from the sea. It was second nature to go to sea to help when others were in distress even though they knew of the risk to their own lives.

But, for their womenfolk, with nothing to do but watch and then wait during the long dark night, hearing the sounds of the storm and not knowing what was happening aboard the Northern Belle, it must have been absolutely terrifying.

It’s unlikely that Ann knew that Alfred, aged 25, was among the six who were put aboard the Northern Belle to help the crew through the long dark night.

When did she know that her brother in-law George was the only man to go out three times in the rescue attempt?

Was she there on the cliff when people realised that, of the three luggers, Ocean, Eclipse and Victory, which went out on the rescue mission, only two had returned? The Victory had been swamped by the heavy seas and disappeared beneath the waves. Its nine crew drowned, including William Emptage and his nephew John Emptage.

All those who took part in the rescue were awarded American Presidential Medals and on 31 July 1857, Alfred and the other five who went on board the Northern Belle were presented with their medals. The local newspaper reported:

“It would seem invidious to distinguish one man from another, but we cannot refrain from calling attention to the fact that during the dreadful night of the wreck of the Northern Belle, our hardy Alfred Emptage was the main stay of the crew during the proceedings of that dreadful night; it was he who took the crew and lashed them to the mast, and who during the night, endeavoured to keep up the spirits of his fellow sufferers; he it was who had a willing hand and a trusting heart, although the next wave might have swept him off the wreck.”

We don’t know how many rescue attempts Alfred took part in before or after the Northern Belle but we do know that the RNLI took over the lifeboat service in 1860. Its records show that Alfred took part in three rescue attempts between 1870 and 1871.

Both Alfred and his brother Edward were aboard the lifeboat Quiver in January 1871 when the brigatine Sarah went aground on Margate Sand having been caught in a strong easterly gale. The rescue attempt took over three hours as the brigatine was continuously swamped by the sea.

So the rescue of the crew of the Northern Belle wasn’t the only time that Ann would have joined the wives and families of mariners, worrying and waiting, as their men fought the waves in atrocious conditions during rescue attempts.

Perhaps the women who had grown up in the mariner families around the Isle of Thanet accepted it as part of their lives. Or, at least, became resigned to it.

Ann’s husband came from several generations of mariners. All six of Alfred’s brothers who survived to adulthood became mariners. Six of her children’s seven male cousins who survived to adulthood either joined the Royal Navy, the Merchant Navy or became local mariners and lifeboatmen. It was the life they knew.

For the mariners, boatmen and fishermen it was not only a difficult and precarious life but also a dangerous one when they were at sea in bad conditions. Plus, if the weather was so bad that they couldn’t put to sea, they would lose income. Their wives not only had the job of keeping the family clothed and fed on sometimes limited money but probably also had the job of gutting fish and preparing it for market. They may also have mended the fishing lines and nets.

But Ann’s ancestors were not from the sea. Her father was a malster in Canterbury. He and his siblings had been baptised in Blean, a small village three miles north of Canterbury. She knew that there could be a life away from the sea.

I can’t help thinking that it was through Ann’s influence that just one of her sons briefly worked as a boat man and another had a short spell as a mariner before they both switched to other occupations.

Perhaps Ann was also concerned about her daughters, worried that they too would become wives of mariners, leading the hard life that such women led, herself included.

Between 1853 and 1875 Ann and Alfred had seven sons and four daughters. Four children died in infancy or childhood but the other seven survived to adulthood.

Alfred had a brain haemorrhage and died in 1875 aged just 44. Read his story here.

The studio photograph of Ann was probably taken in 1877. She appears to be dressed in black with a black cap denoting that she was in mourning. The white collar shows that it was the second year of mourning.

Ann remained in Margate and died aged 50 in 1882, from an abdominal tumour. So in 1882 the children were free to start new lives. Again, I wonder how much Ann influenced them. Had she discussed their future lives with them? Had her eldest son, Alfred James told her of his plans? Had she encouraged them?

Alfred James (1854-1910): having initially worked with his father as a boatman, Alfred became an assurance agent. Aged 28, shortly after his mother died in 1882, Alfred and his new wife emigrated to the USA where he worked for the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company, rising to become a Vice President of the company. Read his story here.

Edward Lindsay (1856-1886): became an errand boy and by 1881 he was a labourer. A year later, at the time of his marriage he was a mariner. The couple remained in Thanet and had three children including one who died in infancy and one who was born after Edward had sadly died when he was just 30, from rheumatic fever and encephalitis. At the time of his death he was a carter.

Henry Thomas (1858-1896): became a carter and moved away from Thanet. Henry had a very complicated life. He died from pleurisy brought about by a work accident in London when he was just 38. He left a young family. Read his story here.

William John (1864-1907): became a labourer, married and remained in Thanet. His life was also complicated and is explored in Henry Thomas’ story.

Rose (1869-1952): was just 14 when, in 1884, two years after her mother died, she left England to join her brother Alfred in New York. She remained single. Read her story here.

Frances Alice (1871-1929: was 16 when she emigrated to California, USA, in 1888. She too had a complicated life but married and died in California in 1929. Read her story here.

George Geoffrey (1875-1941) was born shortly after his father died. His mother died when he was just seven years old and his eldest brother emigrated in the same year. In 1888 he was one of the orphaned children sent to Canada as part of the child emigration movement. Aged 13, his name appears on a list of workhouse children sent from England to Canada in 1888 by Dr Barnardo. By 1900 he had joined his brother Alfred and sister Rosa working for the Metropolitan Life Assurance Company.

Susan Morris says:

“I have the utmost respect for Ann Phoebe Emptage nee Hopkins and the life in which she found herself through her marriage to Alfred.

Researching family history generally answers questions such as who, when and where. It’s not so good at the how and why questions. I’d love to know, considering that Ann lived in Canterbury and Alfred lived in Margate, how they met.

I was astonished when I discovered that my mother’s ancestors were mariners as she had always hated the sight of ships in films or on tv programmes tossing about on waves. Perhaps she was channelling her great grandmother’s feelings about the sea.

The sea may have skipped a few generations in our branch but it is still in the family’s genes as Ray Emptage, one of our research team, is a keen recreational yachtsman.

Both Ray and I are 2 x great grandchildren of Ann and Alfred, descended from their son Henry Thomas.”

The Shipwreck of the Northern Belle

The Memorial to the crew of the lugger Victory who last their lives in the rescue attempt

The ancestry of Alfred Burnet Emptage

Humphrey Emptage c1725 – 1789 and Catherine Pearce/Pierce

Henry Emptage 1754 – 1836 and Susanna le Brush

Humphrey Emptage 1796 – 1845 and Isabel Brett

Alfred Burnett Emptage 1832 – 1875 and Ann Phoebe Hopkins